Righting the Historical Record

By Jim Hall

Once when I was giving a talk in Richmond at the Black History Museum and Cultural Center, an audience member asked, “How did you get interested in a topic like lynching?”

I have studied, written and talked about lynching for several years, so I had heard that question before. Even so, I struggle to answer it. I’ve said that I don’t really understand my interest, but that seems unsatisfactory, as if I had never examined my motivations.

In Richmond that day I surprised myself by replying with an answer that I had never given before: “Harry Byrd,” I said.

I grew up in Northern Virginia in the 1950s and 1960s, read the newspaper daily and followed current events. To me, Byrd was the evil overlord, omnipresent and more powerful than any one person should be. He was the former Virginia governor who moved to Washington and the U.S. Senate in 1933 and ruled Virginia from there for another 30 years. His racism doomed us, I believed. He was the embodiment of a Virginia that enslaved, disenfranchised, segregated and lynched Black people.

Byrd was also a central character in covering up Shedrick Thompson’s hanging in Fauquier County in 1932, the subject of my first book, The Last Lynching in Northern Virginia: Seeking Truth at Rattlesnake Mountain. Byrd went out of his way to deny Thompson’s lynching and squelch any meaningful investigation, all in service to his political ambitions. If I could expose his sinister maneuverings while telling the Thompson story, I was happy to do so.

But the more I’ve thought about my continued interest in lynching, the more I believe it’s born of something else, something both base and admirable. First the base part.

I learned early on that whenever I mentioned the word lynching, people paid attention. I saw that in 2001 when I proposed lynching as the topic of my master’s thesis at Virginia Commonwealth University. I see it today when I study the faces of those attending my talks.

There is a car-crash aspect to lynching, a ghoulish impulse to stare, an attraction but also a repulsion. And it has always been so. For about two decades in the late 19th century, lynchings were community spectacles, advertised in advance, and featuring unspeakable cruelties. Hundreds, if not thousands, attended.

When Thomas Smith was lynched in Roanoke in 1893, a mob took him from the local jail and hanged him. The next day the crowd, estimated at 4,000, returned to cut down the body. They carried it to a spot beside the Roanoke River, built a pyre and burned it.

“The flames roared and cracked, leaping high in the air,” the local newspaper reported. Soon “all that remained on earth of Thomas Smith was a pile of white ashes and bits of bone.”

Stories such as this one fit a time-honored formula, guaranteed to attract attention. They usually featured a mix of violence, race, sex, ambition, and fear of the other. They were tales of anarchy, driven by ancient prejudices. But they happened in places near where we live now, and not that long ago. They were stories I wanted to tell.

But if I am the barker, trying to lure crowds into the carnival tent, I am also the honest reporter. At least I try to be. I spent long hours trying to figure out exactly what happened to Shedrick Thompson. My account, based on archival research and dozens of interviews, including with Thompson’s descendants, differed from the story that was widely told at the time and for decades afterward. The county coroner and a grand jury said he hanged himself on Rattlesnake Mountain, a desperate suicide. But my account describes something else, how he was murdered by his angry neighbors.

NOT SOME DEADLY VAPOR

Arthur Jordan, the subject of my newest work, was lynched by a white mob in the middle of the night in Fauquier County, VA, on January 19, 1880. He was accused of forcing himself on Elvira Corder, his White employer’s daughter, and threatening her unless she ran away with him, but through my years of research, I found just the opposite, that theirs was a voluntary romance. They wanted only to be left alone to live in peace

In this way, my interest in lynching is a righting of the historical record. I offer an alternate, more accurate, version of the victim-blaming lynching stories that have been available. That is why I’ve traveled to Berryville, Fairfax, Richmond and dozens of other places to talk about what I’ve learned. I appeared before a church group in Fredericksburg one New Year’s morning to offer this gospel of hope but also warning.

I have seen many wonderful changes during my lifetime; this is a better world in countless important ways than it was when I was a boy. Still, it’s hard to spend any time studying lynching and not see it as part of a disturbing past and forbidding future.

Lynching was not some deadly vapor that descended on Southern Whites and drove them to kill their Black neighbors. Rather, it is one chapter in America’s long history of racial hatred and violence, a history that extends from slavery through disenfranchisement, segregation and opposition to meaningful civil rights.

That hatred is still visible today when far too many express racist views with racist language, when a White police officer murders an unarmed Black suspect, or when a mob storms the U.S. Capitol, builds a scaffold and noose, and displays the Confederate battle flag.

I see it each time I visit the Warrenton Cemetery, where Arthur Jordan was lynched. It’s a beautiful cemetery with more than 8,000 graves, including hundreds of Confederate soldiers. Perhaps the most notable of these graves belongs to Col. John S. Mosby, the legendary “Gray Ghost.” Mosby was a Confederate cavalry officer, cunning, fearless and a bane for Union forces.

What bothers me is that Mosby’s grave is now a shrine. Visitors leave flowers, coins, flags and other tokens of admiration. What is admirable about this man? He warred against his own country, defending a way of life that enslaved and murdered Black people.

I see nothing worth celebrating in that.

ONCE A WEEK. FOR FIFTY YEARS.

Lynching is mob murder, usually, but not always, by hanging. What distinguishes it from other types of murder is that the murderers can count on community support.

Black men were the usual victims, though Black women, White men and even White women were also lynched. Lynching was principally race-driven terror, a powerful form of intimidation. Whites were not about to share power, despite what the new laws said, so Black men were their targets.

Lynching occurred in almost every state, but it was in the South, the 11 states of the old Confederacy, where it became a public sport, a ritual of sacrifice.

The lynching era is a variable concept, though many define it as the 50 years between 1880 and 1930.

The number killed also varies, depending on the period and places studied. All agree, however, that thousands died, probably more than 4,000. Two researchers, Stewart Tolnay and E.M. Beck, put it best: Each week for 50 years in this country, a Black man, woman or child died at the hands of an angry White mob. The numbers still stagger: Once a week. For 50 years.

When lynchers were asked why they lynched, about a third of the time they answered that the victim had committed a murder. For another third, they accused the victim of some sort of sexual contact with a White woman. Of course, lynching victims had no say in any of this, couldn’t defend themselves, and often had done nothing wrong. With few exceptions, the lynchers acted with impunity.

From what I can tell, there were no lynchings in Fredericksburg or in Spotsylvania, Stafford, King George or Caroline counties. In Virginia, the bloodlust doesn’t appear to have been as strong as in other parts of the South. Many reasons have been offered for this, but it seems small comfort to say, yes, we killed more than 112 Black people during the lynch era, but not as many as those guys over there.

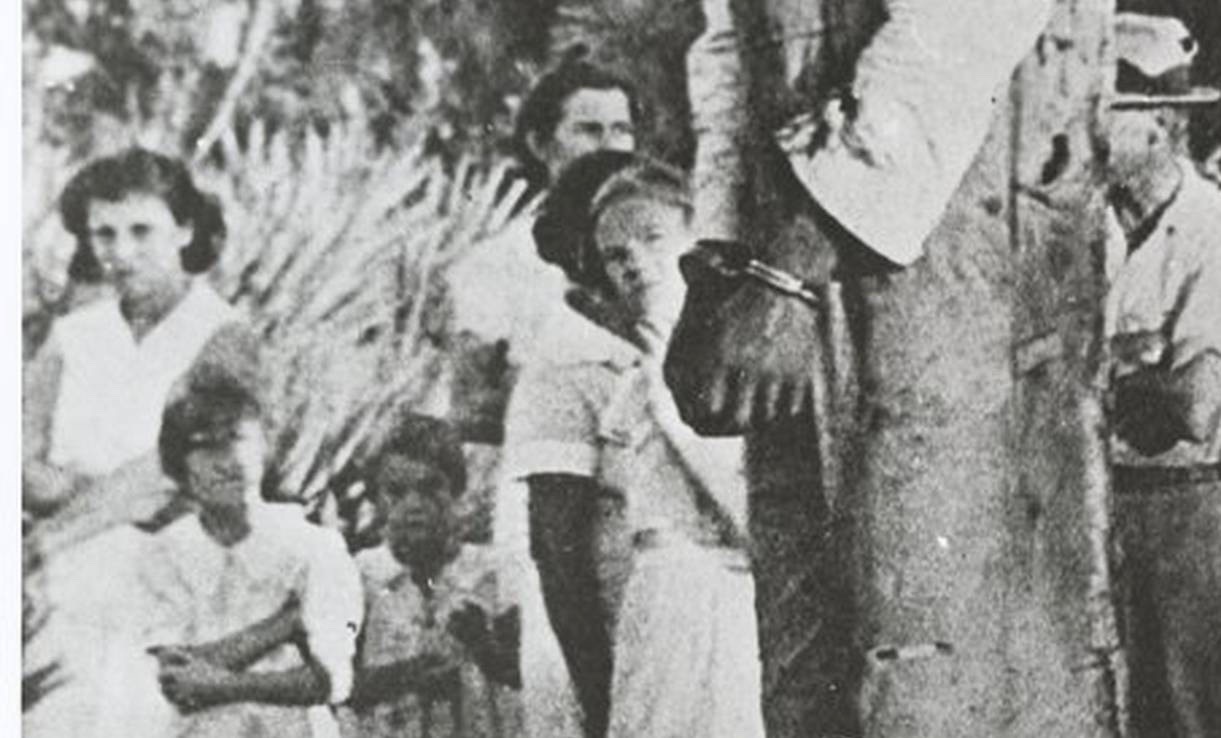

A Fauquier County doctor went to the Warrenton Cemetery in January 1880 to make this sketch of the body of Arthur Jordan

***

Jim Hall is a resident of Fredericksburg and a former reporter/editor at The Free Lance-Star newspaper. His new book, Condemned for Love in Old Virginia: The Lynching of Arthur Jordan, will be published by History Press this summer.