The Past Is Never Dead. It’s Not Even Past.

By Scott Howson

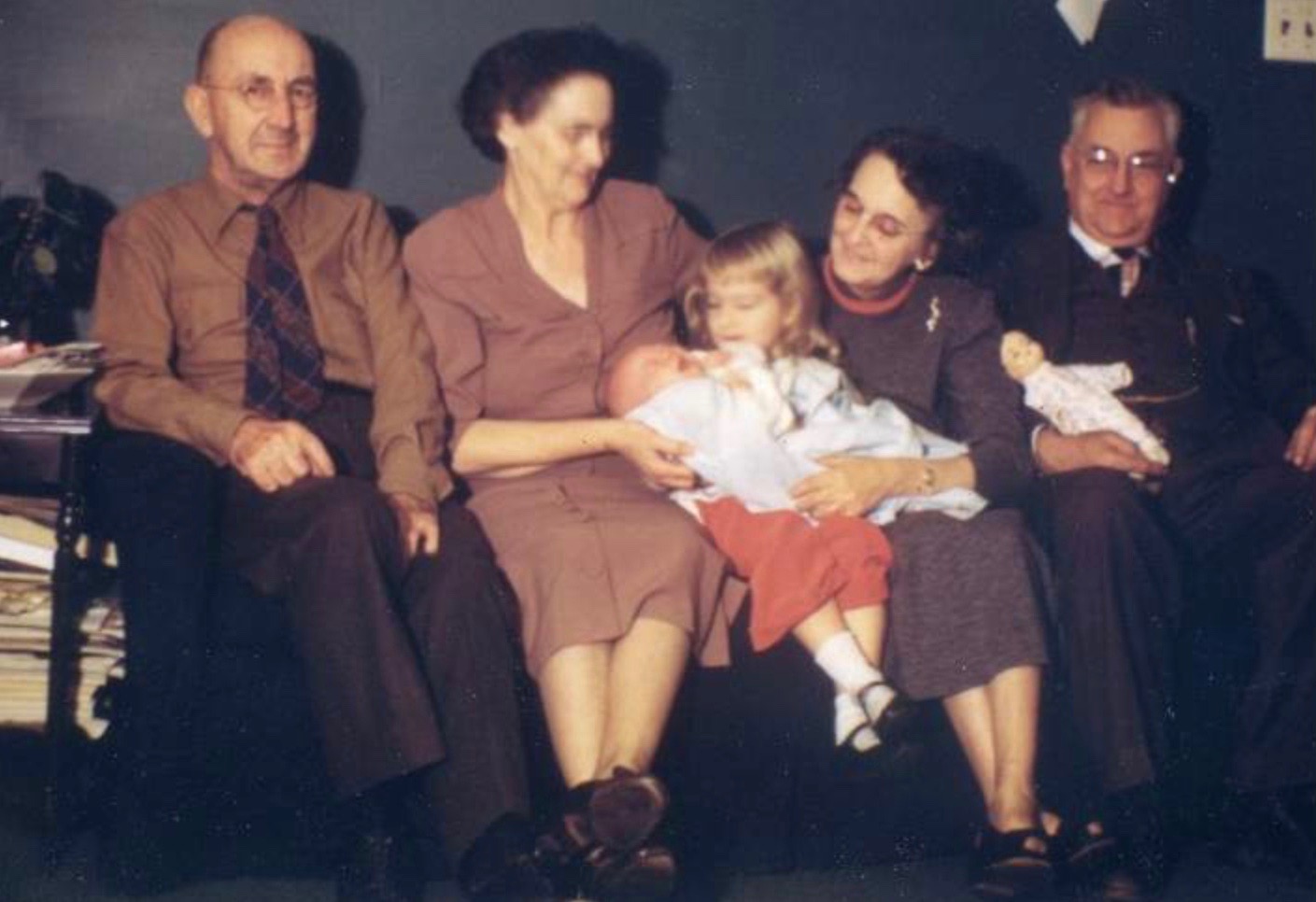

When I was a kid my entire family lived in Louisiana, in a small village of New Orleans called Algiers, to be precise, and as far as I knew that’s where we had always been. I heard somewhere that my grandmother, my dad’s mother, was born in Virginia, but to me Virginia was just another state somewhere I’d never been to. Actually, Virginia was just the name of a state I’d never been to, since I knew nothing about Virginia except that George Washington, Thos. Jefferson and Patrick Henry were from there. I remember my mom had a big crush on Patrick Henry. She saw him give that speech in a movie when she was a teen, I think. Anyway, I didn’t know anything about Virginia the place, so it didn’t much matter that my grandmother was from there, nor did I wonder at all what her life was like before she was my grandmother. It was more interesting to me that my grandfather had been born in England. I didn’t know where in England, though. England was just England.

When I was eight, my family took a vacation, driving from Louisiana to New York in our un-air-conditioned, radio-less 1957 Chevy. During that trip, on one crisp June day, standing on the portico of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, looking over the Virginia piedmont with the Blue Ridge mountains in the distance, my eight-year-old self looked up at my mom and boldly pronounced, “As soon as I can, I’m moving back here.” Years later, after a series of coincidences that in retrospect seem unbelievably remarkable, in my early twenties I found myself living a mile up the road from Monticello, working for the Charlottesville Daily Progress. They had just called me one day and offered me a job heading their graphics department. Like it was meant to be.

While I was working there in Charlottesville one day, I got a packet in the mail from my dad. It was a copy—one of those typewriter tissue paper carbon copies, for those of us old enough to remember such things—of a report on the history of the Clay family that my grandmother had been sent. My grandmother, the one from Virginia, was Mary Esther Clay, and she had been sent this report, compiled by someone at William and Mary, of the history of the family starting with John Clay, English Grenadier, who had landed at Jamestown in February 1613, and then settled at a place called Jordan’s Journey, wherever that was. My family had visited Jamestown during the summer vacation we’d taken in 1959, so I knew it wasn’t too very far from Charlottesville. Not compared to Louisiana, at least. Reading through the report I discovered that my grandmother had been born and raised in Campbell County, on my great-grandparents’ farm near Lynchburg, a place I’d driven through many times on Rt. 29. I’d never thought of Nanny as a young girl, living on a farm before cars and tractors, or even electric lights. I started realizing that she hadn’t always been my Nanny in Louisiana, and that my family’s roots actually ran deep in my adopted state of Virginia.

Skip ahead a few years. I’d moved to Fredericksburg, now in my late thirties, and was having lunch at Sammy T’s with Jay Harrison, a friend and local archeologist. In the midst of our chatting away I asked him if he had ever heard of Jordan’s Journey, where my great-something grandfather had settled in 1613.

Jay told me it just so happened that he was in the middle of a dig there, a state mandated archeology study prior to the building of a residential development on the land. Jay told me that Jordan’s Journey, now called Jordan’s Point, was on the south side of the James River, just east of the City of Hopewell, only 20 miles from where my wife, Sandy, had grown up. So who knows? Our families could have crossed paths for years—centuries even—before she and I finally met and married.

This was all before the Internet, and despite a sincere interest in what my family might have been doing in Colonial Virginia only a stone’s throw from where fate had drawn me to settle and start my family, I had neither the time nor the expertise to do the necessary research to find out anything much about my Colonial ancestors. But that all changed twenty years later when Sandy treated us to a trip to England and Scotland for my fiftieth birthday. Our plan was to visit the places my dad’s family came from, and during what was supposed to have been a quick afternoon stop in Penrith to visit my grandfather’s hometown, I ended up spending two days in the Public Library reading microfilm census data from the 1800s and chasing through the town looking for the places where my grandfather and great-grandparents had lived.

Penrith is a medieval city, the streets laid out like worms in a bait can, and the address numbers on the buildings aren’t consecutive. Building number eighteen can be between buildings twelve and seven. Sandy and I found a man perched at the top of a ladder leaning against one of the brick buildings along Little Dockray and asked him if he knew where we could find #12, my great-great-grandparents’ house. It turned out that #12 was the building he was working on; he’d simply taken down the numbers while he was painting. He told us that before painting the inside he’d taken some photos of the actual rooms my family had lived in the 1870s, and offered to send us copies. Which he did.

I’ve been hooked on genealogical research ever since, and it’s taken me to some strange, and at times disturbing, places.

A few years ago, I read a story about the first African child born in the Americas, a slave, of course, whose parents were owned by a William Tucker. This would have been around 1620, and there was some mention in the article of a connection to Jamestown. I thought that I remembered a Tucker in Nanny’s family tree, the Clays, and sure enough I found a Dorothy Tucker who married a Charles Clay in Halifax County in1813. They were my fourth-great-grandparents. I still wondered if there might be a connection to William Tucker. On one hand, it would be interesting to find another family link to Jamestown, but even more interesting to find out more about what some of my great-grandparents were doing in Colonial Virginia in the 1600s and 1700s.

So, as people do in this age, I did an internet search for Dorothy Tucker’s parents and William Tucker’s children, and started writing down names and dates hoping to connect 1813 to 1620. It turned out William Tucker had been a sea captain, possibly a slave trader, and a real bastard. Besides owning the first slave child in the Americas, he also was one of the big-shots in Jamestown, and at one point organized a celebration of unity with the Powhatan people, inviting the men of the tribe to a feast in Fort Jamestown. He killed about 170 of them with poisoned wine, and then led an attack on their unprotected village to wipe out the women and children. He died in a shipwreck off the coast of Ireland in 1644.

The detestable William Tucker was Dorothy’s third-great-grandfather, and one of my distant forebears.

The further I went down the genealogy rabbit hole, the more connections came to light that connected me with the distant—and notably historical–past:

My fifth great-grandmother was George Washington’s first cousin.

A great-grandfather was executed for treason in the Tower of London in about 1200.

My tenth-great-grandfather, Sir John Savage, was knighted by Henry V at the battle of Agincourt.

Another distant relative, Hugh deVermandois, died in Tarsus during the Crusades.

If the internet can be trusted, my siblings, cousins, and I are descended from both Lorenzo de Medici il Vecchio, and Olaf Erickson, III, King of Sweden in the early 1000s, which, I can assure you, doesn’t mean a thing today. Surely nothing these ancestors achieved has any bearing on my life, although it’s heartening to know that at least some of my DNA came from people who were apparently intelligent and successful.

I also, of course, looked into my Mother’s German family, despite her insisting to the day she died that we were not German but Italian, who, according to my mother, everyone knows are much more artistic and cultured than the Germans. She was wrong. Mom’s father’s family, the Nebes, had sailed over and settled in Ontario, then moved to Detroit, in the 1840s, around the same time that her mother’s family, the Armbrusters, sailed from Germany to New Orleans. Something must have been happening in Germany in the mid-1800s. While I was researching the family in Germany I was contacted, coincidentally, by a distant Nebe cousin who was researching the Nebes who moved to America. We shared information, documents, and photographs. He’s living with his family in the same village the Nebes have lived in as far back as the 1400s. Cousin Deiter and I remain friends and often share our views on contemporary American politics.

After I hit a wall with my own family’s ancestry, I spent a few days tracking down what I could of Sandy’s family. Like mine there were some lines that went back only a few generations and some that went back eight hundred years. Of course, in truth all our families link back 200,000 years to central Africa, but unfortunately we know the names, places and dates of only a small fraction of that. By the way, remember William Tucker, the slave owning sea Captain from Jamestown? He’s Sandy’s tenth great-grandfather, too, which makes Sandy and me eighth cousins.

Genealogy changes your perspective of the past. In school, we’re taught history event by event. Columbus “discovered” America. Jamestown was settled. The colonies were formed, independence was won, etc. But even if textbooks reported these events accurately, that’s not how history happened. History is the endless succession of generations, day by uneventful day. The movements of families, the development of civilization and improvement of living conditions. This is how history flows, but its pace is set by generations, not events. Those of us able to trace our roots see all of that as we study the progression of generations in our own family trees—not literally, of course, but illustrated across the span of time in a way that recitations of “historic” events can not. Genealogy tells the story of how we got here better than any history class.

It also gives us a sense of how different our lives are today from everyone who’s ever lived before. For tens of thousands of years, until very recently, the world that people lived their entire lives within, with very few exceptions, was limited to a few miles of where they were born. Most people were not aware of other global cultures in other parts of the globe, nor were they aware of the scientific and creative advancements, and “historic” events that we study in school. The tools they used, the clothing they wore, foods they grew and ate, and even the houses they occupied and the buildings they knew, in other words the details of their lives, were the same as their grandparents and great-grandparents. And most probably would be for their children and grandchildren.

The richest people in the world only 150 years ago—200,000 years into the development of humanity—couldn’t get ice cream in any flavor they wanted whenever they wanted and wouldn’t even dream of crossing the ocean in a single night. All of our ancestors struggled just to keep their families alive, threatened by disease, crop failure, wild animals, and enemies. We, on the other hand, live in climate-controlled houses and travel effortlessly in comfortably upholstered seats, yet complain if Wegmans doesn’t have our favorite flavor of cream-filled cookies this week. Compared to our great-grandparents, we live like royalty, thanks in large part to the perseverance of our ancestors to whom we should be forever grateful.

Yet, people today are in many ways the same as everyone else before us. We still love our families and struggle to protect them and make their lives better. Most of us work hard at our jobs every day without expectation of achieving fame. We seek comfortable shelter. We still wonder if there is a Supreme Being in control of all this, are still awestruck by the majesty of nature, and still enjoy stopping for a quick chat with a neighbor. And three generations down the line we, too, will be forgotten, and our great-great-grandchildren will wonder how we could have ever survived without whatever gadget will then be occupying their imaginations. Hopefully, God help us, the life we are now passing on to our children will continue.

Knowing the names, dates, and places of one’s ancestors really doesn’t change anything. Whether you know that your fifth great-grandfather was a saddle maker in Devon is irrelevant. But it does open your eyes to where you stand in the parade of humanity. It also helps you to envision the lives of the people who made you who, what, and where you are. The names, places, and dates help you envision what clothes your sixteenth century great-grandmother might have worn, what she might cook for dinner, how she would travel. It focuses the time and place of the characters from your family’s past. Your ancestry becomes real by the simple act of identification, and as your ancestors become real in your imagination, your own life, hopefully, comes more into focus. You are, in fact, simply the current vessel of the life force, and a hundred years from now you will be but one of the many links in a chain that fades all the way back to Creation.

***

Scott Howson is a retired graphic artist and former vice mayor of Fredericksburg, VA, who now spends his time writing stories, recording music, building furniture, playing with his grand kids, and exploring the countryside with his best friend, Sandy.

***

“The Past Is Never Dead. It’s Not Even Past.” William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun