The Gaujot Brothers of West Virginia

By Steve Watkins

They must have been hard up for heroes back in the day. How else to explain the Medals of Honor—America’s highest award for valor in combat—given 15 months apart in 1911 and 1912 to the Gaujot brothers of West Virginia? One had once shot and killed an apparently unarmed fellow soldier and gotten away with it in military court. The other had been court-martialed for water torturing Filipino prisoners and had to pay a whopping $150 fine.

Still, two brothers, Julien and Antoine “Tony” Gaujot. Two Medals of Honor. Doesn’t happen every day. The Williamson, West Virginia, National Guard armory is named after them, and there’s a plaque with their names on it at Virginia Tech, which both briefly attended, though neither for very long. Go Hokies.

I’ve come to know the Gaujots—Tony especially—through research for my book The Mine Wars: The Bloody Fight for Workers’ Rights in the West Virginia Coal Fields, scheduled for publication in May 2024 by Bloomsbury Press. And while I can confirm that the brothers were undeniably gutsy and did some heroic things, they were also manifestly cruel and violent men who left a trail of dead and broken bodies in their wake, including, in the end, their own.

The younger Gaujot, Tony, got his Medal of Honor first—for swimming across a rain-swollen river in the Philippines while pulling a canoe with his teeth (well, a rope attached to the canoe) so his men, pinned down by Filipino insurrectionists, could cross the river to safety, or to counterattack, though as it turned out the canoe was never actually used for either one—or at all. By one account, as many as 80 guerrillas shot at Tony while he held his breath and swam the whole way underwater, one of their bullets wounding him in the shoulder. By another account—Tony’s own—he wasn’t hit (and it’s highly doubtful the ill-equipped Filipinos had all that many weapons to begin with), but he later claimed the action put a strain on his heart from which he never recovered. Not that it stopped him from later becoming one of the most ruthless anti-union gun thugs for the notorious Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency in the coal fields of West Virginia, where he busted union heads, evicted union families from their company-owned homes, and fired a machine gun for hours down at striking miners during the fabled Battle of Blair Mountain until his weapon melted and he had to abandon his post.

When Tony received his Medal of Honor—a very long 11 years of bureaucratic entanglement after the heroic swim—his older brother Julien, still in the Army, vowed to get one for himself, and was heard to say of his brother’s award, “He wears it for a watch fob, the damned civilian. I’ve got to get one for my own self, if I bust.”

Which Julien promptly did, for negotiating the surrender and release of Mexican Federales surrounded by a band of Pancho Villa’s fighters during the Mexican Revolution, though Julien and his troops—he’d been promoted to captain by then—had been assigned to guard the Arizona border and steer clear of the conflict. It’s true that Julien put himself in considerable harm’s way to do what he did. In a hagiography posted on Virginia Tech’s website, Julien is said to have ridden across the border on his beloved horse Old Dick “into the teeth of the revolutionists’ fire… [s]pouting Spanish profanity, at which he was an acknowledged master.” Other reports say Julien, accompanied by an American businessman, just had to cross a street to get to Mexico—the Arizona town of Douglas, where all this happened, straddled the border—then walk a quarter mile to negotiate the soldiers’ release. Julien’s commanding officer said the action “warranted either a court-martial or a Medal of Honor.”

What’s also true is that when he wasn’t saving Federales’ lives, the heroic Julien was busy overseeing a quasi-sanctioned military brothel, and 10 years earlier, during the Philippine Revolution where he and Tony were deployed to quash the indigenous people’s rebellion, he took part in the aforementioned water torture of prisoners.

“If a captured Filipino refused to divulge military information, four or five gallons of water were forced down his throat until his body became ‘an object frightful to contemplate.’” That’s how one historian described the technique used by Julien and his fellow torturers. “Then the water was forced out by kneeling on his stomach. The treatment was repeated until the prisoner talked or died. Almost all of them talked.”

In a typo-riddled dispatch from the Philippines, U.S. Army General Adna Chafee tried his best to downplay the atrocities, saying the torture was necessary because what the other side was doing was even worse, and American lives were at stake, etc. Shades of Abu Ghraib:

“Sorely impossible convey in words correct idea difficulties been met with by officers in prosecution this war, nor can President fully comprehend that very much necessary success would have failed of accomplishment had not serious measures been used force disclosure information. Some officers have doubtless failed in exercise due discretion, blood grown hot in their dealings with deceit and lying, hence severity, some few occasions. This regretted.”

Julien pleaded guilty, though the sentence couldn’t have been much lighter: three-month suspension from command duties and a $150 fine, which was one month’s pay.

Just before younger brother Tony was sent home from the Philippines, he, too, was found guilty of, well, something—an unspecified violation of an unspecified article of war that also cost him a month’s pay, though it didn’t prevent him from being promoted to sergeant just before being mustered out of the Army.

It wasn’t the first time Tony had been in trouble. Not long after enlisting a few years earlier—in Williamson, West Virginia, in 1898—he was brought up on a charge of “Murder, to the prejudice of good order and Military discipline” for killing a fellow soldier. The allegation was that Tony, acting in some capacity as an MP, “in attempting to arrest Private Frank Scurlock… [did] secure from the tent of his Captain without the Captain’s Knowledge [sic], a revolver, and going to the tent wherein the said Private Frank Scurlock was, shoot him with the said revolver, in the neck.” Scurlock died a week later. Military justice being the oxymoron then that it still is today, Tony was somehow acquitted. He was even given a two-week furlough to visit his mom, who’d been worried about what might happen to him if he was found guilty of murdering the now-late Private Scurlock. He’d spent a month in military jail while awaiting trial and was sent off to fight in the Philippines a year later.

Violence followed the Gaujot brothers wherever they went. Later the same year they enlisted, Julien was “accidentally shot” on Christmas Day “in line of duty” while still stateside. No other details were included in his military record, except that he obviously survived. Tony, not to be outdone by his older brother, was shot in the right foot—“not in the line of duty”—shortly before the brothers were deployed. No other details were included in his service record either, except that he was out of commission for a month while the unexplained gunshot wound was given time to heal.

The Gaujot brothers had been born into a life of privilege. Their French-born father, an engineer, was in high demand at mining operations all over, and spent a year as general superintendent of mines in Japan where the Japanese emperor awarded him the honorary title of “general.” He later became chief engineer for the United Thacker Coal Company in Mingo County, West Virginia, a place that would figure prominently in the annals of American and West Virginia labor history and is a principal focus of The Mine Wars.

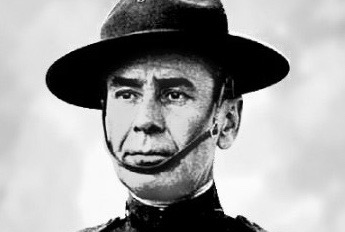

Historian Merle Cole described Julien Gaujot as 5’8”, 125 pounds, with dark complexion, brown eyes, black hair, and an anchor and star tattoo on his left arm. That was when Julien was 24 and a captain in Company K of the 2d West Virginia Volunteers. Tony, four years younger, was described by Cole as 5’5”, 129 pounds, “fair complected, with brown eyes and hair, and a scar across his nose and forehead.”

Weirdly, in his book The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom, historian James Green says Tony Gaujot—known as “Tough Tony” or sometimes “Bad Tony” to the union miners of the Mountain State—was “a six-foot-four, two-hundred-pound man who wore a black bowler hat to cover an oddly shaped head topped with a bump about the size of a baseball.”

Either way, Tony went on to make a name for himself in the West Virginia State Police and with the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency keeping tabs on the coal miners, which largely meant doing whatever the mine owners and operators deemed necessary to keep the United Mine Workers of America from organizing the underpaid, overworked, tightly controlled labor force in West Virginia. Tony’s brutal tactics and fierce leadership skills, possibly picked up from his time in the military, first drew attention during the Paint Creek/Cabin Creek Strike of 1912-1913, where he led hundreds of heavily armed mine guards in a campaign to crush the union drive in the Kanawha Coal Field mines.

After a break for a return to the Army and service in the Great War—where he was joined by thousands of the coal miners whose rights he’d done everything possible to deny—Tough Tony Gaujot came back to West Virginia and took on a leading role in yet another conflict, this time with the state police and the mine owners’ private army in an all-out war against 20,000 angry workers at the Battle of Blair Mountain.

Hail the conquering hero.

Julien spent his adult life in the military. Tony pinballed through stints with the state police, the Army Reserve, a sheriff’s department, and, finally, in the mines as an engineer, though the only thing clear about where he may have gotten his training or education is that it wasn’t at Virginia Tech.

Things didn’t end well for the once-celebrated Gaujot brothers.

In 1935, a “semi-invalid” Julien, by then retired from the Army, moved back to Williamson, West Virginia, where Tony was already living, and took up residence at the Mountaineer Hotel with his 15-year-old son, James. A year later, the violence that had followed the Gaujot brothers all their lives caught up with them again.

A West Virginia Historical Society Quarterly article titled “Soldiers of the New Empire: The Gaujot Brothers of Mingo County,” tells what happened:

“At about 4 p.m. on April 13, 1936, Tony went to the hotel to visit Julien. When he encountered James in the hall, they got into an argument about what the boy had done with a check his father had asked the boy to cash. James—reportedly ‘hot-tempered, high strung, and … laboring under the impression that he had been grossly maligned by his uncle’—pulled a .25-caliber Spanish automatic pistol. He chased Tony into an empty room and shot him three times, then ran to his room to reload. A hotel porter encountered James in the hallway. He reported that the boy ‘looked over at him and smiled and started back toward his own room, gun in hand.’

“Tony had crossed the hall to his brother’s room and called the desk for an ambulance. Julien was laying in bed reading. While Tony was still sitting at the telephone, [James] returned and fired three more shots, one of which struck Tony in the left side and knocked him to the floor.”

Two bellboys managed to wrestle the gun away and hold onto James until police came. Tony was rushed to the hospital with five bullet wounds. Four bullets were still in his body, one of them pressing against his spine. He held on through a couple of surgeries and transfusions until a little after midnight. Doctors said it was hopeless from the start. James, after a surprisingly short stint in prison, was killed in a plane crash a few years after his release.

Julien died of pneumonia in 1939, alone in a Virginia sanitarium, two years after his brother. They buried him in Arlington National Cemetery, Tough Tony back home in West Virginia.

Tony Gaujot

***

Steve Watkins is co-founder and editor of PIE & CHAI, a professor emeritus of English, a longtime tree steward with Tree Fredericksburg, an inveterate dog walker, a recovering yoga teacher and co-founder of two yoga businesses, father of four daughters, grandfather of four grandsons, and author of 15 books, two of which are forthcoming in 2024. His author website is http://www.stevewatkinsbooks.com/.