A Memoir

By Steve Watkins

“There is a land of the living and a land of the dead,

and the bridge is love, the only survival, the only meaning.”

–Thornton Wilder, The Bridge of San Luis Rey

The Aravalli Range

ONE/The Aravalli Hills

I spent the last night of my first life on the stone floor of a small cave high in the Aravalli Range, deep in a wildlife preserve, a winding 60 kilometers south of Alwar, a small city of a hundred thousand in dusty northern India. I had been traveling through Asia for four months—India, Nepal, Thailand, now back in India–smoking too much hashish and struggling to eat the spicy foods. It was early December 1976. I’d dropped 20 pounds since the end of my summer job as a laborer in a Central Florida phosphate mine, but hadn’t had much of an appetite for weeks. I also had a deep, wracking cough that had started two weeks before, traveling west from Calcutta back to my friend David’s Peace Corps village in Rajasthan province for a final visit before returning home to America, or what was left of it in that bicentennial year.

The coughing kept me awake much of the night, but didn’t seem to bother the sadhu who sat nearby, tending his small cave-fire. Every time I dozed, and then woke, he was still sitting a few feet away, gazing at the glowing coals. He was impossibly thin, dreadlocks covering his bare shoulders, nothing on besides a loin cloth. When he saw me watching, he pressed folded hands to his forehead and nodded. Strange shadows danced on the cave walls behind.

David, whose village was 20 kilometers to the west, said the sadhu had taken a vow of silence and hadn’t spoken in five years. He only left his cave to offer prayers at a temple nearby. We’d brought food the day before when we rode rented bicycles down from Alwar—choking on dust from a handful of trucks and buses we encountered on the trunk road to Sariska Wildlife Preserve, then straining as we pushed our bikes up into the hills on the one unpaved, rock-strewn road. Rice and chapatis and curry. Dried beans. Spices. All sat partially eaten in bowls next to the fire.

The cave and temple, isolated deep in the heavily forested hills, were at the base of Pandupol, where David said Hanuman the Monkey God was believed to have punched his fist through the side of a mountain ages before to unlock an underground river, creating a natural bridge with a spring and waterfall flowing free to save the Rajasthan families from drought.

He had insisted I do the hospitable thing and stay the night with the sadhu, while he rolled out his sleeping bag under the stars. For the past two years he’d mostly slept on the roof of his home in his village. He said it made him claustrophobic without that sky and without those stars. We’d heard stories about tigers in Sariska, and killer baboons, but after all that time in rural India, David wasn’t bothered. If something was going to happen, it would happen, and if not—thank Hanuman, Krishna, Buddha, Jesus, luck, whoever, whatever.

That’s how I remember it anyway—the memory as vivid as I write this as if it were just now happening, decades later. The cave. The stone floor. The sadhu. The fire. David off somewhere else, under the stars.

But David says there was no cave. That’s a false memory born of the trauma that happened the next day—a hallucination from the injury and the shock. From blood loss. From organ damage. From abdominal infection. From malaria. Pneumonia.

There are other details about that night and the next day that David says I have wrong as well. Yes, it was a hard, stone ground we slept on, and yes, the sadhu sat up through the night tending his little fire, but David was there, too, in his sleeping bag nearby. We were actually both out under the stars. He says my memory is wrong about how far I fell when I crashed the next morning, too, and how long I lay beside the road while he went for help he couldn’t find.

For years I told anyone who asked about the deep and vivid scars that form a crooked cross on my torso and a jagged scissure in my back that I fell off the side of a mountain. David says it was a hill. I remember lying beside the road all day while he went for help. He says it was a couple of hours. I can still picture how dark it was when I was finally rescued. David says it was early afternoon.

***

In the morning, at the first hint of light—as I remember it, anyway–I crawled out of my sleeping bag and pulled myself up off the stone floor. I felt bruised all over. Everything was stiff. The sadhu was still next to his fire, squatting, staring, contemplating, praying, chanting silently. I stiff-legged my way out of the cave, careful to trail a hand on the wall to keep from stumbling. Then I had to negotiate a narrow set of stone steps to find a path, and a place to pee.

I don’t remember much else about that morning, surprisingly—right or wrong. Did we go to the temple? Were there other sadhus? Did we have breakfast? Chai? Anything? I’m sure I smoked my first bidi of the day not long after waking, though it sparked more coughing, more phlegm, more gasping for breath. I had pneumonia, as it turned out, one lung completely congested, but wouldn’t know that until X-rays much later.

There were more stone steps to climb once it got lighter out—back up to the natural bridge at Pandupol. The December morning was crisp and cool so I pulled an old, ratty, thin V-neck sweater over my t-shirt. It used to be my dad’s. I also had on a pair of threadbare white cotton draw-string pajama pants and what was left of my Chuck Taylors after all those long months of travel.

The steps rose up and up through the rocky side of the steep hills, the path squeezed between boulders, turning this way and that until at last, out of breath, we were at the stone arch where we stood without speaking, mesmerized by the forest beauty. The only sound was a small stream and the waterfall, the one that Hanuman made, tumbling down its own stone steps. David said the Aravalli Mountain Range was the oldest in the world–1.8 billion years. The Himalayas, where we’d spent a week trekking back in October, were a mere 47 million, so one of the youngest.

I pulled out my ivory chillum, the one I’d bought from another saddhu, a pothead who also sold me an ashy fistful of pot in Varanasi—and then helped me smoke half of it. The chillum had a baboon carved into the side. Or maybe it was a lion. David pulled a small rock of hash out of his shoulder bag and scraped some off into the bowl. I lit a match.

We didn’t get very high. After smoking so much for the past four months, I was practically immune. That’s what I told myself, anyway. I doubted it had anything to do with what happened next when we climbed back down from Pandupol.

I read somewhere that you have your particular Hindu god who looks after you, and if so, it would have been better for me if that Hanuman temple at Pandupol had been a Ganesh shrine instead. Ganesh had already saved my life once, months before, when I climbed out a window to get off a packed bus in Himachal Pradesh because I had to go to the bathroom really bad and didn’t want to wait until everybody else–and their goats and chickens and babies and bundles–got off first. We were only stopping for a few minutes, in the foothills of the Himalayas, on the mountain road to the town of Manali in the Valley of the Gods, and I needed enough time to find some privacy so I could take a shit.

When I dropped to the ground, though, I stumbled and pitched backward toward the side of the road and the dense brush that I didn’t know masked a sheer drop over the edge of a fifty-foot cliff.

Somehow, defying laws of physics, I was able to right myself, and immediately was surrounded by people from the bus who grabbed my arms, as if I might turn around and jump deliberately, or be unsteady enough that there was still danger of falling. They pointed across the road, to a small shrine. David appeared next to me and explained–it was Ganesh, and he must have saved me. My fellow passengers sang and exclaimed and prayed loudly in thanks for the miracle.

***

It was late morning by the time we said goodbye to the sadhu, and goodbye to Pandupol. I smoked another bidi and fought through another bout of coughing. We shouldered our packs and climbed back on our bikes, old, rusty clunkers with coaster brakes and no gears. I felt unbalanced.

David took off ahead of me. He’d been leading the way for most of the past four months, since he was fluent in Hindi and knew the people and the culture, so of course he would today as well. I followed, flying fast down the dirt and gravel road out of the Aravalli Hills. We were going back to David’s village. We would return to Alwar after that, where his friend Shankar lived now with his new bride. We’d been guests at their wedding the week before. We would take the train to Delhi after Alwar, stay a few days with another friend at the American embassy, eat American things—French toast, pizza, cold beer. And then home.

As much as I’d wanted to leave America back in the summer, now I was eager to return, worn out from the incessant cough and shortness of breath and dysentery. I missed my off-again, on-again girlfriend Robin and hoped she missed me, too. I missed my family. It was the same old pattern. When I was home, all I could think about was how much I wanted to be away. When I was away, I couldn’t stop thinking about home and how much I missed it. I was tired of the hard travel. Tired of being reminded I didn’t belong here, another privileged Westerner, another tragic pilgrim. They hadn’t invented India so I could come here and find myself. I was just a visitor, just passing through, and needed to tread lightly, disturb as little as possible, find ways to give more than I asked to receive.

My last shift at the phosphate mine, the day I quit to go to India, a guy I worked with said, “Good luck, man. Don’t let Mahatma Gandhi get you.” Two nights later, I was staring down at the black Atlantic Ocean from my tiny airplane window. It was the middle of the night, but I couldn’t sleep. I’d never been out of the country before. Hardly ever been on a plane. The sky cleared and there was a full moon. I saw the lights of ships, but mostly nothing, just the infinite trembling of the waves.

***

Maybe I was more stoned than I realized. Maybe I was too weak from the weight loss and undiagnosed pneumonia. Maybe I just wasn’t watching closely enough to where I was going, except the back of David on his bike, twenty meters ahead of me. I pedaled faster to catch up. There was another steep hill with a sharp turn. I hit a rock.

The front wheel went sideways, jerking the handlebars loose, and I was in the air, holding on to nothing, my pack flung to the side as I catapulted off the road, into space, the ground dropping away beneath me as I flew off the side of the hill. A bed of rocks rushed up at me. I covered my face and hit hard, slamming helplessly onto those rocks.

In my memory, as I replay the moment, it takes such a long time—tearing down that road behind David, hitting the rock, flying over the handlebars, falling and falling and falling, lifting my hands not to brace myself, or wrap around my torso as I should have done, but to protect my face—that the possibility exists that I might never land. But of course, with no Ganesh across the road to bend the laws of physics and save me again, I did.

There was searing pain in my abdomen. Immediate, explosive, all-consuming pain. A black hole of pain, and I disappeared inside it. I remember black, a long tunnel of black, then raging light and raging sound that was me screaming, clutching my belly, rocks cutting into my back, my side, my arms and legs. One of my ribs—probably the 12th rib, a floating rib, on my right side–had bent instead of breaking. The sharp anterior end—connected to nothing–had torn a three-inch gash in my liver. Blood and bile gushed into my abdominal cavity.

But I knew none of that at the time. I only knew the pain—the way the world becomes nothing else but that pain, that blinding pain, the sum of existence in those terrible moments.

And then there was David somehow lifting me, carrying me back up the steep hill, climbing the rocks with me back to the road. David holding onto me as I thrashed wildly to try to escape but couldn’t. David laying me carefully on the gravel and holding me and telling me over and over that I wouldn’t be able to escape from this, that I had to go to where the pain was instead—not try to flee from it, but run toward it, go to the pain, breathe and go to the pain, breathe and go to the pain, keep breathing and go to the pain. He said it over and over and over as he held me. He said it was the only thing to do.

***

The back of my right hand bled for a while. Then stopped. I wasn’t aware of it at the time. David told me later. The pain, slowly, miraculously, mercifully, flattened into something heavy, with dulled edges. I couldn’t speak. I remember sobbing then, my face pressed into David’s shirt, as the realization of what had just happened swept over me, with this understanding that in that moment of carelessness, or distraction, or clumsiness, my life had changed—radically and forever. David tried to sit me up, but when he did the blackness overwhelmed me again, and when I regained consciousness I was lying down, still in the road, the gravel digging into my back.

“Try it again,” he said when I opened my eyes, and again lifted me into a seated position.

But I kept passing out every time he raised my head above my heart. There were no visible marks besides some bruising and the blood on the back of my hand. But clearly something was wrong.

“I have to find help,” David said. I nodded, unable to speak. The sun was above the trees now, so it was late morning and growing hot on the road. David found my pack, which had been flung loose when I crashed. He laid out my sleeping bag in some shade on the grassy side of the road and slid me over on it.

“I have to leave you here,” he said.

I might have nodded. I might have managed to say something. I didn’t want him to leave me, but I couldn’t think too much about it. I had to concentrate on where the pain had been and where the heaviness had set in. I had to be vigilant. I couldn’t let my thoughts stray.

David rode off and I was alone. I passed out again. I dreamed, or hallucinated. I drifted in and out of consciousness. I imagined animals coming from the forest. I heard things. Leaves rustling. The wind in the trees. I heard the sunlight, felt it burn my face when the shade no longer held.

I had to take a shit. I didn’t know how I was going to do it. Somehow I rolled off the sleeping bag and pulled down my pants and managed to squat without passing out, holding on to a fistful of grass to keep from falling. I lost the ring I was wearing. Dropping so much weight so quickly, even my hands and fingers were too thin.

I had to find the ring. I finished shitting—the last time I would go for the next two weeks. I pulled up my pants and blindly patted the ground in search of the ring until I found it. Seven metals, thin filigrees of gold, silver, copper, I didn’t know what. Probably tin. Probably the metalsmith who sold it to me was blowing smoke up my ass about how rare it was, and about what it symbolized. I had bought it for Robin, to give her when we were together again, if we were meant to be together, back in the States.

I slipped it on my finger and made a fist so it wouldn’t slip off. Crawled to the sleeping bag. Waited for David or Death.

TWO/The Bardo

“In bereavement, we come to appreciate at the deepest, most felt level exactly what it means to die while we are still alive. The Tibetan term bardo, or ‘intermediate state,’ is not just a reference to the afterlife. It also refers more generally to these moments when gaps appear, interrupting the continuity that we otherwise project onto our lives…. But to be precise, bardo refers to that state in which we have lost our old reality and it is no longer available to us. Anyone who has experienced this kind of loss knows what it means to be disrupted, to be entombed between death and rebirth. We often label that a state of shock. In those moments, we lose our grip on the old reality and yet have no sense what a new one might be like. There is no ground, no certainty, and no reference point—there is, in a sense, no rest. This has always been the entry point in our lives for religion, because in that radical state of unreality we need profound reasoning—not just logic, but something beyond logic, something that speaks to us in a timeless, non-conceptual way. Milarepa referred to this disruption as a great marvel, singing from his cave, ‘The precious pot containing my riches becomes my teacher in the very moment it breaks.’”

Pema Khandro Rinpoche, “The Four Points of Letting Go in the Bardo,” The Lion’s Roar, 29 November 2022.

***

I lay on the side of the Sariska road continuing to fade in and out of consciousness. Dave had to ride several rough, winding miles to the trunk road where he hoped to flag down someone, anyone, with a vehicle. But the odds weren’t good. There weren’t many private cars in rural Rajasthan, not much traffic of any kind in either direction south of Alwar, not much chance that a truck or a bus would leave its route to help, should one even come along. David might have to travel further, maybe even the full sixty kilometers to Alwar. I didn’t know any of this at the time, just that he was gone for hours. Midday sun burned my eyelids, making it impossible to open them without turning my head, but I didn’t want to turn my head, to move at all, out of fear that even the slightest movement would trigger a return of the lacerating pain in my abdomen. The longer David was gone, the more I despaired.

The accident played itself over and over in my mind–the surge of terror when I hit the rock and my front wheel jerked sideways, losing my grip, flying over the handlebars, forever falling. Dave was always saying “Up jumps the Devil”–when things seemed to be going smoothly, so smoothly you made the mistake of taking them for granted, and maybe you didn’t pay enough attention, or maybe you did pay attention but it didn’t matter, because you couldn’t control everything anyway, and so something happened because something always happens.

The line repeated itself in my head like a mantra. I tried to focus on my breath, to breathe deeply, to distract myself from the black void at the edge of my consciousness, but it hurt too much, whatever was broken inside stabbing like shards of glass into my diaphragm.

I kept seeing things that weren’t there. Hearing things. Threatening sounds. More animal noises. A wheezing engine. The crunch of gravel. An ancient bus straining up the hill and past me, inches from my sleeping bag. How strange. A bus, here. And how strange for them to see me, a firangi, taking a nap on the side of the road.

David finally returned with a young Indian on a motorized scooter. “You’ll have to sit behind him,” he said. “He can take you to Alwar, to the hospital. But you’ll have to hold on yourself. Can you do that? I’ll follow on the bike and meet you there. He knows where to go.”

“Sure,” I responded. I wanted to be helpful. I didn’t want to be a bother. But when Dave pulled me up to a seated position, I was immediately slammed by a wave a vertigo. Everything went black again. He tried a second time, and a third, and a fourth, but the vertigo crashed over me even harder and I blacked out each time. The scooter-wallah looked on helplessly.

Dave grew desperate. “You have to try, Steve. We have to get you out of here. We have to get help.”

But I couldn’t. What little strength I had I’d used up shitting and fumbling in the grass for Robin’s ring. Mostly, though, there was too much internal blood loss, though we couldn’t know it at the time. Maybe Dave suspected. He finally gave up. Sat down beside me and held my hand.

“This isn’t going to work,” he said, more to himself than to me. “But I don’t know what else to do. There was nobody else on the trunk road that would stop.”

I’d never heard him like this. America Dave, as kind as he was, and with so many friends, as warm and generous, as fun to team up with on the basketball court, always seemed a little lost, lonely at times, even when others were around, even with me. It would be years before I understood how depression worked, and how hard Dave had had to battle all his life to ward it off, or to survive at its worst when it threatened to overwhelm him. As a boy, he had been thrust into the roll of caretaker for his mom, who insisted he call her Pauline, and who drank to mask her own depression. He remembered her as kind and loving and smart and funny—and as slurring her words when he brought friends over and embarrassing him, as falling down and him finding her passed out and helping her into bed before his father came home. It was important that they pretend everything was okay. Dave found where she hid her bottles of liquor and emptied them down the drain. She cursed at him and bought and hid more. His brother stayed away at friends’ houses, at his girlfriend’s. His father worked late at the high school, or buried himself in his second job, building and repairing watches and clocks. Dave looked after Pauline.

India Dave was different. A pilgrim, searching, just as he’d always been back in the States, but more self-assured here, at home in the wider world. I’d grown used to him knowing what to do, where to go, how to get there, what to say and how to say it.

I wanted to reassure him, but I was having trouble finding the words. I tried to tell him that I’d be all right here. I tried to thank him for going for help. I tried to tell him I was sorry for this mess we were in. I couldn’t be sure what I actually said. I might have been crying, but I was too dehydrated. Dave lifted my head, urged me to drink water, but most of it dribbled out. I had difficulty swallowing because I was so parched. He persisted. The scooter-wallah spoke to David in Hindi. Dave gave him some rupees and he left. Dave laid me carefully back down.

I remembered the bus. The hallucination of a bus. But it hadn’t stopped. Why wouldn’t it stop? Couldn’t they see I needed help? I said these things to David, and must have made enough sense that he understood.

“Are you sure?” Dave asked, with something like hope in his voice. “A bus? Going up to the temple maybe? To Pandupol?”

“No,” I said. “Not sure. Maybe not. But I thought so.” I had no idea whether it was real or something I imagined. I was confused about everything. I just wanted to close my eyes. I was too tired, too off, to be sure of anything.

Dave hiked back up to Pandupol, a mile deeper into the Aravalli Hills, where we’d spent the night, where we’d left just that morning, though it felt like days ago when we were there. He was gone for a long time, or no time at all. I kept losing consciousness. He returned. He told me that yes, there was a bus. An ancient bus, just as I described it. Filled with Hindu pilgrims, there to visit the Hanuman temple to pray and leave garlands of flowers and offerings of food and alms for the sadhus. They’d taken a different entrance into Sariska from the trunk road. That’s why David missed them when he went looking for help. They would stop on their way back and carry us to Alwar.

It was another hour, two hours, ten minutes, I had no idea how long before they returned. I thought it was night. Everything was in shadows. Everything was so dark. But David says it was only mid afternoon. They threw my broken bicycle on top of the bus. David must have gone back to the trunk road at some point to retrieve his, and it was thrown up there, too. He got another man to help him carry me onto the bus, convinced the driver to let us sit near the front, though one of the pilgrims refused to move and stayed wedged into the seat next to us. David propped me up, held onto me the entire trip from Sariska to Alwar, even for another hour-long stop at another shrine on the way, though Dave begged the driver to skip it, told him I might be dying.

The man who refused to move his seat kept nodding off and slumping against me, his head dropping onto my shoulder. I tried to push him away. Dave tried to get him to sit up. Nothing worked. We steeled ourselves for the bumpy ride.

Every pothole we hit made me groan in pain. I so desperately wanted to sleep, but my mind was spinning, careening from random thought to random thought, utterly disconnected, except for a continuing sense of foreboding. Something awful was going to happen to us. I tried to tell Dave, but I was still not making enough sense for the words to get through. I didn’t know where we were. There were lights, like a city, finally. We were in Alwar. The driver stopped at the bus station to let us off. Dave bribed him to take us to the hospital. Everybody got off. Someone carried me from the bus. They laid me on a stretcher in the middle of a dusty street.

I asked Dave what time it was. He said it was still late afternoon, but I didn’t believe him. Everything was so dark. They brought me inside.

There were doctors and lights, but no diagnostic tools. They gave me morphine and a blood transfusion. David might have donated his blood. I can’t be sure. He might have told me this. I was too far gone into shock to know anything, though once the morphine kicked in, once the new blood coursed through my veins, replacing what I’d lost to internal bleeding, my mind began racing. We were in a hospital. But why were there palm trees, and why was the floor made of sand? People were speaking Hindi all around me, though I couldn’t see them. But I understood what they were saying. They were whispering. Conspiring. They were going to kill us. They were discussing their plans. They were going to use machetes. There were lights strung up in the palm trees. I couldn’t see who was whispering, who was conspiring. I tried to tell Dave. I wasn’t sure if the words came out right. He was with me, holding me, saying reassuring things, but he had to be hearing it, too.

“They’re going to kill us,” I managed to say. “I can hear them. Can’t you hear what they’re saying?”

Dave said he could and he couldn’t. He said it was all going to be okay. He said I should close my eyes and try to rest, that he’d stay with me. He would take care of things. He would be there when I woke up.

But I never slept. I don’t remember sleeping. I remember an endless night of paranoid hallucinations, an overwhelming sense of dread, a dim awareness that my life had spun out of what little control I might have ever convinced myself I had.

***

My paranoid hallucinations at the hospital in Alwar gradually lessened during that first long night, like a receding tide, leaving me still awake, still unable to sleep, but spent, empty, hollow. Wide-eyed but unseeing. When David spoke to tell me what was happening–the doctors had no way to find out what damage I might have done inside; we would have to wait and see if I healed on my own–I just nodded. I didn’t speak for the first few days. Not much, anyway.

There were no palm trees, no string of lights, no sand, no conspirators, no machetes. Just a large, open ward with dozens of beds, all of them full, most with families camped out on the concrete floor next to them. There were unemptied bedpans, flies coming in through open windows, occasionally rats scampering across the room. Some doctors and nurses came and went. Only once in a while did they stop to check on me with their limited English and my nonexistent Hindi.

Nicholson Baker’s 1988 novel The Mezzanine takes place during the course of a man’s trip up an escalator in an office building. He’s on his way back to work at lunch after venturing out to buy shoelaces. Time slows to an excruciating pace for him that’s filled with random thoughts and associations, the sort of stuff that runs through anyone’s mind in any few given moments. In the protagonist’s stream of consciousness, it’s how cardboard milk cartons came to replace glass milk bottles, why plastic straws float, how vending machines work, the secret to paper towel dispensers, lists of things, computations, digressions, digressions from the digressions, on and on and on, with footnotes that run sometimes for pages. And at the end, a long footnote about footnotes.

Those first days for me in the Alwar hospital were something like that, only not as literary. Not literary at all. I was barely sleeping, day or night. Trying to will my body to heal itself, though I still had no idea what was wrong with me. I kept slapping myself—figuratively, anyway. Chastising myself for my lack of discipline. Why wasn’t I using my time productively, practicing meditation, deep breathing, instead of spinning off into memories of old TV shows, banal conversations, people I’d barely known in the first place and would never see again. The number of places I’d lived in my life. The number of schools I’d attended. The number of girls I’d been with. How Pa on The Waltons wouldn’t go to church with the family. The night Robin and I caught a peeping tom spying on us in her trailer and I ran outside to chase him. An afternoon when I was a kid getting a coke from a soda machine at a gas station and without thinking about it spat into a soapy bucket of water. The attendant, who’d been washing a car, yelled at me and told me to never show my face around there again. The disproportionate shame and embarrassment of that stuck with me for years, long past any reasonable statute of limitations for such a minor transgression.

The hours crept by. Torturous. Only so much slower that even writing it suggests.

After two days, and an occasional injection of morphine and a second blood transfusion, when I could finally stand and take more than a few steps without thinking I was going to pass out, I made my slow way the length of the ward to the washroom. The floor in the stalls was smeared with feces, stained with urine, vomit, diarrhea. I filled a metal cup with water and splashed one as clean as I could get it, then squatted over the hole, clinging to the wall so I wouldn’t lose my balance on the footholds. Nothing happened. My abdomen was distended, though I hadn’t eaten anything since Sariska. I made my way back to my bed, past the kind, staring faces of the families and fellow patients, who had likely never seen a firangi there. I tried not to stare in turn at the terrible burns and missing limbs and swollen faces and feverish children.

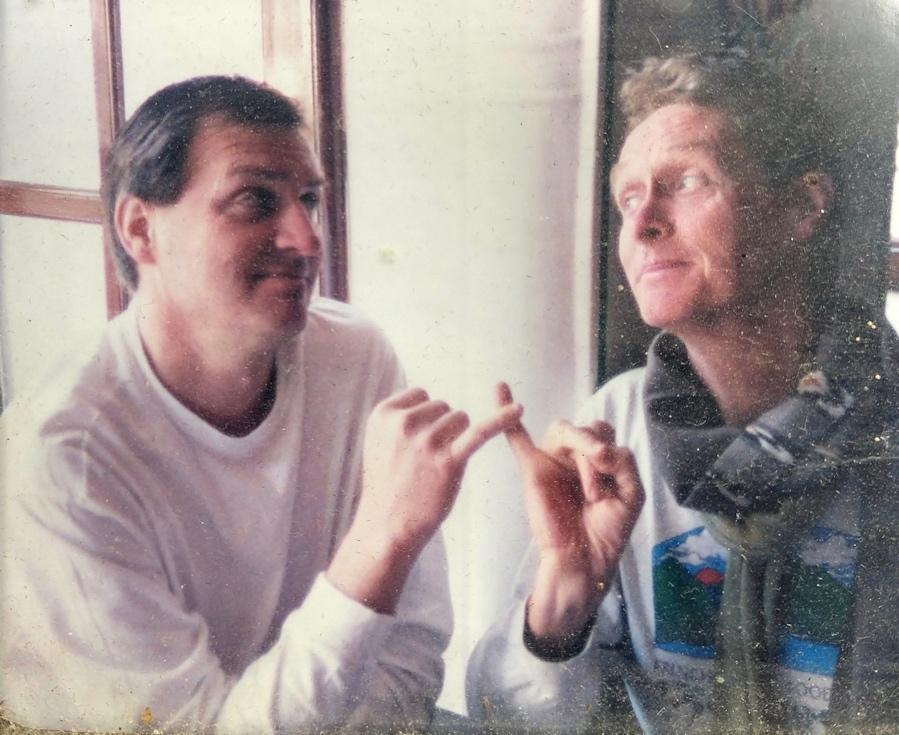

David came and went while I rested and slept and tried and failed to shit. Dave had met a Sikh woman at Shankar’s wedding a week before the accident, a sardarni, Shirim, the younger sister of a friend in Alwar. Now back in the city, they met in secret for walks, to talk, nothing more than that, but still something that wasn’t done without permission from the family, and without chaperones, and without the promise of marriage.

Shankar visited me, filling in for Dave during those seemingly endless days as I alternated between fitful sleep and a kind of stupor where I could acknowledge visitors, even speak to them until I grew too tired, but wished they would leave as soon as they got there. Shankar, who spoke fluid English, was thoughtful, and kind, and he meant well. He was melancholy about his new role and responsibilities as a husband, and serenaded me with Leonard Cohen songs he had memorized when he’d gone off to college in New Delhi before returning to Alwar. “Suzanne.” “Sisters of Mercy.” “So Long, Marianne.” He had his brother, a cook at a curry stand near the hospital, bring me chai and hard-boiled eggs, which I did my best to eat, though I had no appetite, and could barely hold anything down.

The wedding had been in Ramgarh, Shankar’s ancestral village an hour away. David and I were there as “Foreign guests of honor,” which was embarrassing since we hadn’t brought extravagant gifts, which were expected, or any gifts at all, and we were dressed like scruffy hippies while everyone else was decked out in their best suits and saris. We tried to make up for it by giving more rupees than we could afford on the money tree, and by joining in the groom’s party procession that night, the baraat, with movie-star-handsome Shankar in a dark three-piece suit and gold crown riding a white horse garlanded with an explosion of flowers and garishly sequined harness and saddle. Shankar’s friends, many of them stumbling drunk, kept stopping the procession to dance to a couple of caterwauling bagpipes and sticks and rattles and the incessant beat of double-headed drums called dhoi as we made our slow way through the village.

Shankar’s friends gave us safas and garlands, dragged us out into the middle of the dirt street to dance with them while Shankar sat frozen on his horse. There didn’t appear to be any electricity in the village, so everyone in the baraat carried torches, adding an element of danger. But somehow, two hours late, we finally arrived at a small, rented hotel, which might have been the only one in Ramgarh, where a very loud generator fired up an impressive string of lights in the courtyard, and where we met Shankar’s bride and her family. Shankar had never seen her, though he did know her name–Pushpa–but that was about all.

The ceremony went on for hours. Speeches and songs, ceremonial dancing, the money tree, presentation of the veiled Pushpa, a table laden with Indian desserts as excessively sweet as always. I could barely force myself to nibble the edges. Everybody was friendly and gracious and wanted to talk, though few spoke any English, so I was clueless as usual about what they’re saying. I did my best to shower them with compliments about the ceremony, the food, the decorations, their hospitality. There was a lot of smiling and nodding on both sides, followed by polite withdrawal. David, meanwhile, talked to Shirim, who reminded him that they’d met before, in Alwar, where her family lived and where she attended technical college. She told Dave she had long wanted to speak with him, but had been too shy.

I didn’t have a watch, but it must have been three in the morning by the time we climbed back on the wedding bus for the return trip from Ramgarh to Alwar with what seemed to be twice the number of riders crammed into the seats and aisle as had been with us on the way there. I ended up standing the whole time, with nothing to hang onto, thrown against others, and others thrown against me, bruised every time we took a curve on those pitch black rural roads. For most of the way to the city, under cover of darkness, Dave surreptitiously held hands with Shirim.

***

I was happy for David, at least–as I lay in the hospital, and the interminable days somehow passed, and I knew I wasn’t getting any better. I felt guilty enough that I’d fucked up what was left of our trip. We were supposed to fly back to the States in another week. Why shouldn’t Dave get to enjoy himself in the time we still had? I convinced myself, or tried to, that I would be all right, that whatever was wrong inside me would fix itself, and we’d make our way back to New Delhi, and make our flight back to America in time for Christmas. The battery dies on your car, sometimes all you need to do is clean off the terminals and get a jump start.

But that magical thinking didn’t last. I couldn’t hold onto any thought for very long as I mostly stayed in that version of sleep that never feels like sleep. A half-consciousness. A gray half-existence. My body wasn’t healing itself. It was shutting down. My mind seemed to be shutting down, too. I tried to go to the pain, the way David had said, tried to find the exact place where the pain had been, as if that could repair whatever was broken inside. All I found was a continuing sense of dread I couldn’t shake for what was happening to me, and for what was still to come.

I didn’t have the energy to read, or write in my journal. None of the Vonnegut or Tom Robbins or Michener or Frank Herbert I’d been reading seemed relevant anyway. Even my fantasies about being with Robin again came to seem forced, and needy, and pathetic, and pointless. I had nothing to offer her anyway. Not really. And I had nothing to say to anyone here. I felt as though I was sinking deeper and deeper into the thin mattress pressed into the rope bed.

A week passed. I woke sometimes to find Dave looking at me, deep lines of worry etched into his face. Other times I saw him across the ward in huddled conversation with doctors, nurses, the crowd of curious bystanders who materialized whenever something, anything, was happening. Still other times I’d wake to find myself utterly alone. Every night at the Alwar hospital was a dark night of the soul. I was frightened and lonely, desperate for whatever faint hope I’d feel with the first light of morning.

Finally, on a gray afternoon, Dave came back from his last walk with Shirim and said it was time to go. “We have to get you to New Delhi,” he said. “We can take the train tonight. The doctors keep saying how concerned they are, but they can’t do anything more to help. They think you’re stable enough to travel, but shouldn’t wait any longer.”

I nodded, wondering if there was more he wasn’t telling me. But no matter. If we got to New Delhi, we could still make our flight back to the States. I could be home in a week, and Mom and Dad would be waiting, and they’d take care of me, just like they’d always taken care of everyone else when I was growing up—friends and cousins from broken homes, abused children we hardly knew who had nowhere else to go, my uncle and his family when their overloaded car skidded off the side of a mountain road and they lost everything they owned. Maybe now it was my turn.

Art credit: Pixabay

THREE/The Art of Zen

Shankar came to say goodbye the night we left the Alwar hospital, and to bring us food Pushpa had prepared for the journey. It was already dark. David had to carry our backpacks out to a waiting cycle rickshaw. I didn’t know how he managed to get me up into the seat, or down again when we arrived at the Alwar train station. There were no sleeper cars in first class–David doubted I’d be able to handle the usual mass of humanity jammed into third or second–but he was able to get us a private berth with cushioned bench seats, and he helped me lie down on one, hoping I’d sleep. But the lurching of the cars, the clatter of steel wheels on the steel track, the discomfort of my distended abdomen kept me awake. I wanted to apologize. I felt bad about wasting the money on first class.

I spent much of the night propped up in a corner, staring out at moonlit fields and ghost villages, much as I had on my first overnight train trip months before, north from Delhi to Pothankot. I felt years older. All the color had been washed out of the world. Everything was hidden in shadows.

A week since the accident, and I was still chastising myself for having been so careless riding down from Pandupol the morning of the crash, so uncoordinated, and stoned, and stupid. For not having the reflexes to jump free, the way they do in the movies. For not paying enough attention to Alan Watts. “When a cat falls out of a tree, it lets go of itself,” he wrote in The Way of Zen. “The cat becomes completely relaxed, and lands lightly on the ground. But if a cat were about to fall out of a tree and suddenly make up its mind that it didn’t want to fall, it would become tense and rigid, and would be just a bag of broken bones upon landing.

“In the same way, it is the philosophy of the Tao that we are all falling off a tree, at every moment of our lives. As a matter of fact, the moment we were born, we were kicked off a precipice, and we are falling, and there is nothing that can stop it.

“So instead of living in a state of chronic tension, and clinging to all sorts of things that are actually falling with us because the whole world is impermanent, be like a cat.”

***

Delhi Station was its usual chaos, though it was early morning when we arrived, the platforms swarming with thousands of travelers with their oversized bundles and frightened children and crying babies bound to their mothers. David couldn’t find a porter to help us, and he couldn’t leave me to carry both backpacks out of the station to find a taxi or tuk-tuk or cycle rickshaw. “You have to walk,” he said. “Just off the train and out of the station. Stay close behind me. We’re going to have to fight our way through.”

He charged onto the platform and through the station, pulling me along as well as he could, hauling both our packs, at times swinging mine in front of us to clear a path. I kept my arms wrapped around my torso, as though I needed to hold everything in place as much as to protect myself. Nothing catlike about it. But we made it through, out of the station and into the open air outside the gates.

“American Embassy,” Dave told the driver. He’d sprung for a taxi rather than our usual tuk-tuk. Dave climbed in front. I lay down on the back seat, too weak from the frantic walk through the crowd to sit, bracing myself for an hour crawling through traffic –the thick pollution, the incessant horns, the lurching progress. David reached over the back of the seat and put his hand on my shoulder. Maybe he kept it there to make sure I didn’t roll off the seat, or just to assure me that he was still there, and that we’d get through this together, too.

***

Dave’s friend Bob Tetro, who worked for the Foreign Agricultural Service at the embassy, had the guards let us into the heavily fortified compound. I had met Bob once before, after we’d returned to New Delhi months earlier from Himachal Pradesh and Kashmir, before Nepal. He greeted us warmly once again, only this time instead of offering us cold beers, he took one look at the shape I was in—gaunt, wasted–and instructed his cook to make us French toast with a dusting of powdered sugar and real American maple syrup from the embassy canteen. I was thrilled, but had to give up after a few bites. I still had no appetite, a week since the accident, and everything I swallowed felt leaden. Dave, who always ate as if he’d been starved, finished off his and mine. Bob, clearly worried, made some calls while we ate and got me an appointment with a physician associated with the embassy.

Another taxi ride later, this time through wide, paved streets in an opulent part of New Delhi, we sat in the doctor’s examination room. He was Indian, trained in England, and spoke with a familiar lilting English flavored with a Hindi accent. I expected all manner of diagnostic equipment, but the room was bare except for an empty exam table. We sat in chairs. He asked me to show him my hand, and I reached forward with my right, the hand with the now-healed scar, in my confused state thinking he wanted to see my one visible wound. He pinched one of my fingers and studied the reaction. It had been pale but still pink. When he pinched it, the end of my finger turned white and stayed that way. I couldn’t feel anything.

“You must go to hospital right away,” he said. “There is significant internal bleeding, from the accident. You cannot delay. You will need surgery immediately. I will call East-West Medical Center and tell them you are coming so they can prepare.”

***

Things happened quickly after that. I remember them laying me down again in the back seat of a taxi. David urging the taxi-wallah to drive faster through the city. A walled compound across a busy road from what Dave said looked like an overgrown golf course from the days of the Raj. A thick bank of pink bougainvillea. Nurses waiting with a wheelchair at the entrance to a white two-story building. A sign. East-West Medical Center.

I started hemorrhaging shortly after we arrived, thrown back into acute pain worse than in the moment of the accident. I begged them to give me something, anything. I was delirious, desperate, thrashing on the bed. David held me, told me to hold on, hold on, it would be over soon, but it wasn’t true. They had to summon an anesthesiologist. They had to prepare the operating room. They had to find a second surgeon. They needed blood for a transfusion.

They say when pain gets too great you’ll pass out, but that must be a lie, just like the other lie they teach you–that God never gives you more than you can handle. Pain, extreme pain, centers you. Pain reduces you. Pain obliterates you–the ego you, the self-conscious you, the counterfeit you, the caring you.

Finally, past finally, they ran an IV line into a vein and flooded me with anesthesia. There was none of that counting backwards from. There was instantaneous escape. Oblivion. Some people wake up during their surgery, but they still can’t move, can’t speak, can’t communicate. They’re traumatized in their mute and frozen helplessness. They may even suffer pain from the operation, or imagined pain from what they can sense or see is being done to them. But there was none of that for me. I was plunged into merciful nothingness, not knowing if I would ever return from that place, not caring as I was crashing under, only grateful that the pain was subsiding, killed or just temporarily masked, and if the cost was my consciousness, maybe only for a while, maybe forever, I didn’t care about that, either.

***

Dr. N.P.S. Chawla, the Sikh surgeon who owned the private center, supervised the procedure, as he had supervised and performed hundreds of emergency surgeries before mine. A stern figure in his white dastar and tightly trimmed beard, Dr. Chawla had come to New Delhi from Lahore after partition in 1947, and soon after developed a practice doing emergency rescues. He had dealt with his share of wrecked Westerners, starting with his first case in 1970, when the American ambassador flew him on a private plane to Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh to bring back a tourist from the States who had been electrocuted riding on the roof of a train.

I learned all this later, of course. Realized that David and I had ridden on that same train, a few weeks before my accident, had sat on that same roof.

The incision started just below my sternum in my right quadrant and ran nine inches, almost to my pelvis. After the incision, Dr. Chawla pulled back the skin and cut through several layers of fat and muscle and tissue. Working carefully around a three-inch tear in my liver, he removed two-liters of blood and bile, fibrinous clots, and what in his limited surgical notes he described as “purulent material.” Full records weren’t kept, but he likely used peri-hepatic packing–laparotomy pads he tucked around the lacerated area of the liver in hopes that the pressure would stop any subsequent release of fluids.

Or he may have used the Pringle Manoeuvre–named for the medical researcher who developed it in 1908, not for the saddle-shaped potato chips sold in round cylinders–affixing a clamp on the hepatic artery to temporarily stop the flow of blood to the liver.

Or he may have decided that the laceration had already closed sufficiently on its own so that my body could absorb and dispose of any more blood and bile that continued to leak from the damaged area.

They gave me another blood transfusion, my fourth since the accident–most of it donated by Dave. Dr. Chawla cleaned the wound and the abdominal cavity with a saline solution, then inserted two drainage catheters that clogged immediately and didn’t work, then or ever. Stainless steel sutures with bent prongs were used to close the deep layers of tissue.

The surgery took several hours. My family still didn’t know what had happened, and wouldn’t for another day, when they finally received a State Department cable from the embassy. Dave hadn’t had time to contact them since we arrived in New Delhi, and he was afraid to leave during the procedure. Dr. Chawla had told him I was fortunate to have lived so long without treatment, and that I might not survive the operation.

Dave was waiting when they brought me back from the recovery room, unconscious but alive. Still there when Dr. Chawla came in to check on me hours later. The anesthesia was just beginning to wear off, though not so much that I felt anything. Not yet, anyway. The pain would come later. Dr. Chawla felt my pulse. Checked the thick dressing covering my sutures. The drainage tubes. The IV. My eyes flickered open, and when Dr. Chawla saw, he spoke to me in what I would come to understand was his typical blunt fashion.

“You must thank your friend,” he said. “You would not be here if not for him. He saved your life.”

***

David took care of me at East-West Medical Center, opening the windows when I was hot, closing them when I was cold, going for the nurses when I got too feverish or when the IV line backed up or when the fluid bag ran out. Putting his own life on hold for weeks, months as it turned out, to help save mine.

They didn’t have me on any monitors–there weren’t any in the hospital–and the nurses from the Catholic training hospital in Goa, as kind as they were, were busy hurrying from recovering patient to recovering patient. My overwhelming feeling, to the extent that I felt anything, had awareness of anything, had it in me to care about anything besides my own suffering, was helplessness.

So it was David who stayed close, sleeping on a cot in my room. David who lifted me onto a bedpan. David who cleaned me afterward. David who was there in the middle of the night when I woke up confused, delirious, crying. David who was with me when they pulled out the drainage tubes that hadn’t worked, leaving me queasy and shaking. David who tried and failed to coax me to eat something, anything. David who held me and talked to me and urged me to breathe, to relax, to let go.

And David who was with me when I hemorrhaged again, three days after the first operation. The reopened laceration sent me writhing in my sweat-soaked bed and screaming from the same deep, crippling pain I had had on the rocks in Sariska. There was no going to the pain this time; it was nowhere and everywhere. Frantic calls were made. Another surgeon, Dr. Kucheria, was summoned. Dave and a surgical assistant were sent on a desperate search across New Delhi to find a blood bank in the middle of the night for yet another transfusion that would hopefully work through yet another operation. Dave had already given me as much of his own blood as they’d let him.

I was only dimly aware in my fragmented consciousness. Dave wrote about it a few days later in his journal:

Stephen having an acute attack of pain and drop in blood pressure, followed by high fever around midnight. Sucking down a pint of O+ after an hour’s search for a vein to plug, and then only able to prick a small one. Also tried other arm for glucose, but no go. The time passes, sometimes quickly, and sometimes hardly at all. Steve in so much pain and confusion. I’m concentrating on him, but the pain lingers and his willpower is quickly drawn away. Breaking out in hot and cold sweat. Losing control. Slinging off sheet, rolling in terror from side to side, taking a shit on bed. Nurses checking temperature and pulse every five minutes.

Young doctor strides in and takes a look and listen, orders a couple of sedatives and says, “You’ll be all right now.” Fifteen minutes later back again and Steve’s still rolling. What to do? Dr. Kucheria appears and things happen. Sends me and the junior doc out for more blood. Standing at the blood bank door. The junior doc afraid to buzz too long. No one comes. I’m not believing. We drive back to get a technician from East-West, an “expert,” so the young doc says. No doubt a capable man, one that can hold his finger on a door bell when someone is in need. Finally, someone answers. Tells us blood not immediately available. We leave the technician to wait for it. Go back to the hospital.

Steve still sweating. Kucheria back in again looking for another vein. No veins for glucose. I feel faint observing the syringe searching for a good vein. I take my seat. Doctor gives up on glucose. Steve slowly drifts away, sweat beading on his brow. Occasional temperature checks bring him up long enough to open his mouth. So far away. Doctor informs me, “Keeping fingers crossed.”

Steve comes around a little. Overwhelmed with fear. “One bombshell after another.” I come down on him. “You’ve come a long way, you know that? You’re awful lucky. You could be dead! You know that too! You have to hold on, you have to take control. Remember ‘Fear is the mind killer.’”

Steve falls out again. Pain, coughing, tossing and turning. “I can’t take this any more.” Tears flowing, crying release, holding each other tight. I’m so run down and tired, feeling hollow inside. At last, technician shows up–in a taxi, with the blood….

Steve finally out of surgery at 5:15, sedated soundly. A repeat of the first operation. Doctor Kucheria explains: “A collection of blood, bile, and large clots equaling 2 liters removed. The oozing must have started the day the tube was pulled. Very toxic fluid, but no pus luckily so the antibodies are working but unable to contain the oozing from the liver wound. When the accident occurred, a blood vessel and biliary tube carrying bile were severed, so when the hemorrhaging started again, the bile also oozed out into the surrounding cavity. There has also been a blood infection….”

***

I was most of a week coming out of the fog of anesthesia and trauma from the two surgeries, confined to my bed with a urinary catheter and IVs for fluid and nutrition, too weak and unstable to sit up in bed, much less stand. Because of the infection, nurses woke me early every morning to draw blood for tests. I cried every time, though I didn’t know why. The blood draws hurt, but in comparison to the liver laceration and the raw incisions, not so much. Sometimes it took several attempts for them to find a vein that didn’t roll or collapse. I was so depleted, sometimes they couldn’t raise a vein at all.

I spent my days sleeping, feverishly dreaming. David came and went. Mostly he spent the night in the room with me, but once I was no longer in immediate danger, he ventured out to send telegrams to my family, to stay the occasional night at Bob Tetro’s, to eat rich American embassy food, to get high with Peace Corps friends still in the city.

He got letters from Shirim, the sardarni in Alwar. She usually wrote him in Hindi, but tried out her English in a poem that was so simple and sweet it did him in.

I always remember you.

I can never forget you.

Wishing happiness for you.

Not only for a day or two,

Not here and there,

Or now and then,

But over and over and over again.

***

Dave had his own worries. Should he write her back? Her family would be furious if they knew. But what if they were to continue? What if he decided to stay in India, to marry her?

His dad wrote to tell Dave his mom had fallen in the shower and had to have an operation for her back. He was sure it was because of her drinking.

He got word that his old girlfriend, who had taken up with another guy before he joined the Peace Corps, had gotten married in September–and then divorced two months later.

He had no idea what he should do with his life when he got back to the States. He just knew that after India, he could never again be who he once was.

He was anxious about me. Forced to spend hours applying for visa extensions, negotiating refunds for our flights back to the States, haggling with the East-West business office, talking me down when I woke up yelling, incoherent, out of my mind with night terrors. In lucid moments, I still had that sense of dread, that something worse was going to happen, and that everything that had already happened had led me here to this broken place, the past four months an inevitable stumble, a fall from a high cliff, a spiraling down from a mountain, a dream of falling where your unconscious mind is supposed to wake you up before you land because otherwise you’ll die in your sleep.

***

They started prescribing me sedatives in the evenings that sent me crashing into dreamless oblivion. I was in constant pain otherwise, but Dr. Chawla, out of concern for the pneumonia and blocked lung, was adamant that I not be given anything that would further compromise my already shallow breathing.

An old school respiratory therapist came in every other afternoon to beat on my chest to loosen the thick phlegm and open my blocked airways–inducing wracking fits of deep coughing that tore at the sutures and sent me into paroxysms of agony. I was terrified the sutures would burst and I would hemorrhage again. I begged him to stop, begged David to make him stop. Wished there was a way to make everything stop.

The days dragged on and on, interminable, with nothing to fill them except this waiting to get better, this hoping to heal. I was back in the desert, two years before, hitchhiking from California to North Carolina but stuck somewhere in Arizona early on, standing for hours in the blistering sun with my thumb out at the top of the on-ramp to I-10, praying no state troopers would come by and kick me off where there would be no chance of a ride whatsoever, not that anybody was showing any signs of stopping as it was. I felt as if I was disappearing, or perhaps I’d already disappeared, or faded so much that I was camouflaged in the dusty landscape. I was in a state of suspended animation, sometimes forgetting to lower my arm even when there weren’t any cars. They say that when you’re hitchhiking you have to trust the road, trust the universe, that no matter how long it takes, how much you despair, if you wait long enough there will always be another ride. I supposed it was true but was having my doubts, looking around for somewhere, anywhere, I might pitch my tent that night if it came to that, and crawl in with my sleeping bag, and try again the next day.

Finally, after several hours, deep into the late afternoon, long after I’d drunk the last of my water, smoked the last of my cigarettes, long after I’d stopped sweating and was well on my way to heat stroke, a slow-moving truck hauling something on a trailer eased its way up and over the rise. He was going so slow I doubt he even needed to use his brakes, just coasted to a stop. On the trailer was a Port-A-Potty. In the truck, the driver had a cooler full of beer and invited me to drink all I wanted. He told me the Port-A-Potty was full and apologized for the smell. “If I go too fast it might fall off, but if I go too slow, with the tailwind, we might get asphyxiated.”

I was four more days on the road before making it back to the East Coast and, finally, home.

It was sort of like that now, at East-West Medical Center, lying there in a state of suspended animation. Hoping somebody would come by and pick me up. Trusting the road or trying to. Waiting for a ride.

Varanasi and the Ganges

FOUR/On Death and Dying

The glass panes in the jalousie windows of my ground floor room at East-West Medical Center were mostly left open during the day, letting in sunlight and lizards and dust. Steady traffic from the busy road outside the hospital compound sounded sometimes like a river, meditative, soothing, and sometimes intrusive and annoying, nails on a chalkboard. The nurses and Dave coaxed me to sit up, first just for a few minutes at a time on the narrow bed, then in a chair. I was still attached to the catheter and IV, so couldn’t go any further, even if I’d been able, which I wasn’t. Being vertical made me dizzy. I tried the old drunk trick of keeping one foot on the floor and one hand on the wall, but it didn’t work. David insisted that I was dehydrated and needed to drink more. He brought freshly squeezed fruit juices from the kitchen. Cups of hot chai. Thin broths that I could sip so I’d at least have something nutritious until my appetite returned. I was still avoiding most foods other than that.

When they finally removed the bandages, I saw the scars for the first time–ragged incisions on the right side of my abdomen that overlapped and crossed, with two smaller cuts from the drainage tubes, punctuation marks down and off to the side. They’d shaved me for the surgeries, so everything was exposed. I’d lost so much weight that I could see the outline of every rib. I touched the scars, thinking that would make them real, would make them mine, as if I, or anyone, would ever want to claim ownership. But all the feeling was gone on the right quadrant of my torso, from diaphragm to pelvis. It was like touching something that wasn’t a part of me any more any more, something foreign. Like the hemiparesis of a stroke victim, maybe. As if the scars belonged to someone else.

Surely over time the feeling would come back. And just as surely over time the scars would disappear, perhaps leaving a faint trace but fading into something hardly noticeable, the way my memory of the accident and all that had followed was bound to fade, would become just another story to tell, but nothing so real as to change my life.

I thought about my brother Wayne, when we were boys. Somebody was burning brush, and Wayne and his best friend took turns jumping over it, not knowing that much of it was poison ivy. The next day at church he complained that he was itching but he didn’t say why. He didn’t want to get in trouble. By that afternoon his entire body had broken out into weeping sores, his face so swollen you couldn’t see his eyes. The doctor was called. Wayne was moved into Mom and Dad’s big bed in their bedroom. Shots were given. The swelling continued. Mom gave Wayne sponge baths to clean off the pus from the sores. She threaded a straw into the narrow opening of his lips so he could drink.

Wayne could barely speak, but managed to say he was afraid he was going to die. It scared me, and I pretended I hadn’t heard. Mom reassured him, and stayed with him every night, sleeping in a chair.

This went on for days, for a week, Wayne in Mom and Dad’s big bed, the poison ivy leaking through the sheets. The sponge baths. The straw to his lips. The misshapen hands that couldn’t hold anything. Whenever she couldn’t be home, Mom had me sit with him, read to him, keep him company, help him to the bathroom, though he had a hard time even standing up and usually missed the toilet.

But the swelling finally went down. The poison ivy sores dried up and went away. Wayne’s features reemerged so he could see again, and he could drink from a glass. His hands could hold a fork and spoon and he could eat solid food. One of the books Mom had insisted I read to him was Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. I’d hated it, hated all of Lewis Carroll, ever since. Wayne never talked about what happened, about being afraid he would die. There weren’t any visible scars. Even the worst of the sores and lesions faded until they were nothing, until they might never have been.

***

After the catheter and IV were finally removed, and once I proved to the nurses that I could totter around my room without collapsing, they let me drag myself up a flight of concrete stairs to shower. I hadn’t bathed since before Sariska, hadn’t washed my long, matted hair, hadn’t gazed in a mirror, hadn’t fully seen what I looked like naked. I braced myself for the shock, but at least I would get to stand, or sit, for as long as I wanted in the hot shower, be enveloped in it, let it wash me clean, and maybe once I was clean, once I washed my hair, once I put on something besides the stained hospital gown, I wouldn’t look as bad as I feared.

I had to pause every few steps to catch my breath. I held onto the wall as I climbed. Thankfully, there was no mirror in the shower room, either, but I could see enough when I stripped off my gown and cotton pajama pants to be dismayed all over again, to wonder how this could be the same body that had trekked for a week at altitude in the Himalayas, that had taken me all over Asia for the past four months, that I’d taken for granted all this time. I could still hardly bear to look at the bold red scars, the stitches that had yet to be removed, the gray stubble, the stark outline of bones.

But just as bad in the moment, maybe worse, was the shower. I turned the faucet handles every way possible, but all that came out of the showerhead was a cold trickle, painful in its own way for the acute disappointment and the shock of it on my sensitive skin. I had meant to lose myself in the rapturous warmth, but I was freezing instead, and there wasn’t even any soap–and I realized, too late, wet and shivering, that I hadn’t brought a towel.

I broke into a fit of coughing–so severe I reflexively wrapped my arms tightly around my abdomen for protection, fearful again that something might tear. My legs gave out and I dropped to my knees, then onto my side, curled up in a fetal position on the cold, concrete floor, still coughing, still holding on, still soaked and naked, spitting yellow-green phlegm onto a clogged drain so nothing disappeared.

***

I wasn’t my best self as the days dragged on. I complained about the food, complained about the temperature in the room, complained that it was too sunny in the grassy courtyard and I didn’t have any sunglasses or anywhere to sit, complained about the blood draws, complained that they wouldn’t discharge me to go to the embassy and recover at Bob Tetro’s, complained that they kept dragging me into taxis for a half hour drive to another clinic for x-rays that showed more fluid building up in my abdominal cavity.

I complained about the ongoing complications, about being bored, about not having anything to read, about not remembering anything I just read. I complained in my journal, when my hand wasn’t too shaky and I could write. I complained to Dave, who mostly listened patiently, even sympathetically, though I knew he was worn out by it all. I complained about the enormous syringe they inserted between two of my ribs to aspirate more blood and bile–a liter the first time, 1200 cc’s the second.

I pissed the bed on accident, compulsively picked my nose until it was bloody, shit myself before I could make it to the toilet when my dysentery flared up, cursed the lack of hot water, refused to take any more cold showers, quit the sleeping pills and stayed up all night, angry at the world.

But I had Zen moments, too, undeserved, seemingly out of nowhere, of something like calm and acceptance. Long conversations with Dave about our friendship, our travels, the accident, the myth of control, the unpredictable nature of experience, Up Jumps the Devil, the wheel of time, the infinite cycle of existence, amor fati–love of one’s fate.

Dave stayed with me through everything, and when I was at my lowest, homesick and depressed on Christmas Day, facing weeks more in the hospital, he coaxed me out of bed and down to the East-West business office, though he wouldn’t tell me why until we got there. “Phone call for you,” he said. They handed me the receiver and I heard my mom’s voice on the other end of the crackly line, and then my dad’s, and my sister Johanna’s. Mom and Jo were crying too hard to speak, except to say how much they loved and missed me. Dad was his usual gruff self. Told me he was proud of me. Told me to thank Dave for all he’d done, for taking care of me through this ordeal. Told me he was wiring money. Told me he wished he could be there to take me home.

Wayne got on last. He had driven down to Mom and Dad’s for the holidays.

“Hey man,” he said. “Looks like Mahatma Gandhi got you.”

***

Death was everywhere in India. I’d seen it as soon as I arrived months before—in the faces of street children in New Delhi, unable to stand, pointing weakly to their empty mouths. I saw it in Kashmir when I set off on my own for a few days from Dave and took a bus from Srinagar to Aharbal Falls at the end of the one paved road into the Pir Pindal Mountains. Halfway there, we got stuck behind another bus on the narrow highway, with no room to pass. The road narrowed even further to a single lane when we entered a village, shops and stalls and pedestrians and bicycles and animals just a few feet away on either side. The bus in front of us didn’t slow down and neither did we, both barreling through with horns blaring. Until the first bus stopped suddenly, forcing our driver to slam on the brakes as well.

We heard screaming ahead of us, a cacophony of hysterical voices. The doors opened and passengers streamed off the first bus, so of course everyone on our bus insisted on disembarking to see what was going on. A Sikh priest, Mahant Singh, who had befriended me early in the trip, urged me to stay in my seat. He and his sons would look into the matter and let me know what was going on, but I was as curious as everyone else and followed them off. As soon as we were on the street, it became clear–terribly, horribly clear–what had happened.

Brain matter and blood dripped down the side of the first bus from the last small triangle-shaped window–barely large enough for someone to stick his head through. Or to pull it back inside quickly enough if there was an electricity pole planted too close to the road. The crowd from the first bus was running now, further into the village, away from the bus and what must be the body of a dead man or woman on the back seat. What was left of the skull may have been thrown inside as well. Or perhaps it rolled under the bus. No one wanted to look. The passengers from our bus followed the other crowd, running now also, as if we’d been ordered, or as if we were being chased. We ended up on the other side of the village, in a field where a man was still screaming, tearing at his clothes, tearing at his hair, his face distorted with anguish as others tried to stop him from hurting himself, from shredding his clothes, from running off again. He must have been the dead man’s friend, or the dead woman’s husband, or just someone who was also sitting on the back seat, one person away from the window.

The distraught man gave up. He collapsed to the ground and sobbed helplessly. Others were crying, too, and continuing to hold him. Mahant Singh coaxed me away from the crowd, and with his sons we made our way slowly back to the buses. He was worried that I was traumatized by what we’d just witnessed, but he was wrong. I was shocked, of course, but also darkly fascinated, drawn to the whole macabre scene, the anguish, the hysteria.

The bus drivers were conferring with what appeared to be officials from the village, though I supposed they could have been anybody, curious onlookers inserting themselves into the scene, adding their voices to the conversation just because they happened to be there.

“There is a problem,” Mahant Singh told me. “This bus–” He pointed to the one ahead of ours. “It will not start again. And it is too far for our bus to back up, and the road is too narrow. The driver says we will have to push this first bus to the other side of the village, to the field, so we may get by.”

No one had attempted to clean the blood and brain and tissue, or to remove the body. Dogs came out to lick the remains, but villagers chased them away out of respect for the dead.

Other passengers returned. The women climbed onto our bus. The men, and men from the first bus, took our positions and together we rolled it through the village while the driver steered in neutral. Mahant Singh kept checking on me, to make sure I was alright. I assured him that I was fine, but we were all shaken. I wondered what they’d do about the body. I wondered what happened to the head, the skull, anyway, and what they’d do about the mess. Would they even continue on the stalled bus once someone could get it running again? It wasn’t as if there were others to take its place.

We reboarded. Mahant Singh ordered several people to move so we could return to our original seats. Nobody argued. He tried to change the subject once we were seated and moving again–to the beauties of Kashmir, the wonders of Aharbal Falls, the majesty of the Pir Pindal mountains, the icy purity of Konsarnog, a glacial lake high above the tree line, the splendors of the one true God. We passed a cow and a bull fucking violently in a pasture. I’d grown up in the rural South, been chased through open fields by bulls, spent hours searching for mushrooms in cow patties, but I’d never seen that before. Further on, we had to wait while a small procession of mourners crossed the road carrying a shrouded body.

***

I’d known a lot of people who died. My infant sister. My mom’s favorite Aunt Missy. A boy everybody called “Big’un” who dove into a shallow creek when I was a kid and broke his neck. A worker who fell from a water tower they were erecting in our little town. A girl I’d just met whose horse was spooked by a passing train and bolted onto the road in front of a speeding car. Veterans from the retirement trailer park, the shut-ins Mom made us visit on Sundays after church when we were little. Dad made Wayne play “Taps” on his Boy Scout bugle at their funerals. My friend when we were twelve who got electrocuted in a pool with an underwater light that wasn’t working. I tried and tried to make myself write a sympathy letter to his mom, but didn’t know what to say and just couldn’t do it. Two guys in high school band, thrown out of the back of a truck. My dad’s friend who shot himself. They said he’d just been cleaning his gun, like Ernest Hemingway. My friend in high school who got in a fight with his parents. He locked himself in his bedroom and pulled a loaded shotgun out of the closet. A girl I had a crush on in tenth grade until I found out that wasn’t her real hair; it was a wig she wore because of chemo. A kid whose mom said she’d buy him a motorcycle if he’d just please get a haircut. A boy in junior high who got kicked in the head by a horse. He told everybody he was fine, but went to bed and never woke up. A girl Wayne dated who went for a ride with a drunk motor head. The teacher in a “Death and Dying” class I took in college who was herself dying. We all went to the funeral, only I was late, and when I ran up the steps to the church, there she was, alive again. It wasn’t actually her, of course. She had a twin. None of us knew. A guy I worked with on an evening shift at the phosphate mine whose wife killed him later that night in a drunken argument. A body I had to wash and toe-tag and bag and wheel to the morgue at a county hospital where I worked for a year in North Carolina, the first corpse I had ever seen, and touched. I managed to close his eyes, but couldn’t force his jaw so his mouth stayed open. I smelled the rotting stench of his cancers and couldn’t scrub it off when I got home after my shift was over.

For reasons I couldn’t explain, those deaths, which were oddly distant then–maybe I was too afraid of my own death to grieve anyone else’s–were closer in India. Death itself felt closer. One night in Varanasi, a week before the accident, I dreamed I was buried alive, or drowning, and woke up gasping, clawing frantically at whatever held me under. But even when I managed to fight my way out of the prison of sleep, the nightmare held me tightly in its grip.

We had arrived late on the train from Bodh Gaya, the village where Buddha received his enlightenment, and were staying in a cheap, windowless room. I was desperate to escape, but I couldn’t see. Couldn’t breathe. I was drenched in sweat, my cotton drawstring pants and white t-shirt soaked through. I felt my way along the wall, finally awake. Felt my way to the door. Flung it open and threw myself into the alley.

But it was still too dark. There still wasn’t enough air. I stumbled out of the alley and onto a narrow cobblestone street that wound its way through a maze of sagging buildings and boarded shops and dark temples, down the steep incline to the river. I stopped there, panting, barefoot, hands on my knees, at the top of the stone slab steps on the banks of the Ganges, where people came during to the day by the thousands to bathe, perform ritual ablutions, do puja–and, as I could see in the dark, a few hundred yards away, to cremate the bodies of loved ones on the open pyres—the ghats–next to the water’s edge, then spread their ashes on the sacred river. Dave said Hindus believed that to die and be cremated in Varanasi would break the cycle of rebirth, would let you attain salvation. But only one in a thousand could make their way or be brought there to their final end.

I didn’t know about any of that. I was just thankful that I could finally see and breathe. I couldn’t go back to the room where David must have slept through my panicked waking from the nightmare. I climbed down the stone steps, to the ghats, which burned all night and were burning then, and watched as ashes of one were taken by a grieving family, while the muslin shrouded body of another waited its turn.

Tired workers wiped off soot and sweat, rewrapped their turbans, then laid the shrouded body on a carefully constructed bed of logs for the next cremation. The fire was set from below, and soon the dried wood was blazing fiercely, quickly burning off the muslin and loin cloth, leaving the body briefly exposed before the hair caught fire and the skin blistered and melted off, leaving the organs to burn away into nothing. Black smoke rose over the ghat and floated above the Ganges, a mile wide there, outlined by a gray sky to the east. It took the longest for the skeleton to disintegrate. One of the workers swung a long staff at the skull to crack it open so the flames could reach inside. And then the ghat-wallahs squatted and waited. There was no hurrying the rest.

I was horrified at first, but couldn’t stop staring. I wasn’t sure what I felt, only that as strange and as awful as it was, I didn’t want to leave. I sat a short distance away, calmer, no longer freaked out by the dream I’d had of dying, and watched and waited with the ghat-wallahs as the bodies burned to ash.

***

A couple of summers before, living at my parents’ house while working in the phosphate mine, I sank into something like a depression–an overwhelming feeling of dread about the obvious truths that my parents were getting older, that they were going to die, that everyone I knew would die, that I would die, that death was inevitable, that there was no Sunday School heaven where we would all be together in eternity, that nothing was permanent except loss. For a couple of weeks, I hardly spoke to anyone–my parents, teachers and classmates when I returned to college in North Carolina, a girl I had been seeing, even my friends Geoff and Lynn, with whom I was living in an old farm house in the country.