A Passage from India

By Steve Watkins

I couldn’t eat the Indian dishes they brought me at East-West, which was all they served. Even the mildly spiced foods made me nauseous. Dr. Chawla said I was malnourished and underweight, that my body was too weak for healing. He insisted that I find something I could eat, so Dave, not knowing what else to do, brought American foods from the embassy canteen: Kraft macaroni and cheese. Nestlé Quik. Skippy Peanut Butter. Ritz Crackers. He had the East-West cooks bring me large glasses of cold chocolate milk–which nobody drank in India. I was embarrassed and grateful, and still managed to eat only a little of the processed foods.

The year was crawling to an end, and my world had shrunk to a small bed in a small bedroom in East-West Medical Center and a small, grassy courtyard outside that I forced myself to circumnavigate, shuffling like an old man, drenched in sweat from the effort. I didn’t have the stamina to do any more. There were no other firangi. The other patients in the courtyard were mostly older Indians, sitting in plastic chairs with families at their feet on picnic blankets. They brought in food, container after container of curries, mountains of chapatis, glasses of chai. Children dressed in their temple best stood quietly, waiting to be noticed, or addressed, or given permission to run around and play, not that there was much room. They glanced shyly in my direction but kept their distance. I didn’t have the strength or the energy to play or even try to make conversation if they came any closer.

I sat in the grass but wasn’t able to stay there very long. It felt wrong, or impolite, to let myself go, to sprawl all the way onto my back and just lie there under the broiling sun. All the chairs were taken. There was nothing to sit on, nothing to lean against. I couldn’t sag back onto my elbows because of the severed abdominal muscles. The only way to straighten myself if I did was to roll over on my side and push back up to sitting, then onto my hands and knees, and from there back to standing. The whole process left me exhausted, frustrated, embarrassed. So I mostly stayed in my room.

X-Rays showed that my diaphragm was displaced, an inch or more higher than where it should be, meaning I was still losing blood and bile, meaning fluid was still collecting in my abdominal cavity, likely in a pocket hidden behind one of my lungs, which was partially collapsed. I wrote in my journal that I felt as though I was just hanging on by the skin of my teeth. Only what I mistakenly wrote instead was, “I feel like I’m just hanging on by the skin of my death.”

But David refused to let me despair. In addition to the food, he brought music whenever he could, cassettes and a tape player he borrowed from embassy friends, albums I’d already been listening to for a couple of years, but new to him. The Eagles, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, David Bowie. “Lying Eyes.” “One of These Nights.” “Physical Graffiti.” “Wish You Were Here.” “Young Americans.”

He played them over and over, and talked about all the concerts he couldn’t wait to see once we were back in the States.

Dave and I owed our friendship, or at least our introduction, to a concert. More specifically, to Bob Dylan and The Band–and my brother Wayne, who scored me two tickets for their sold-out January 17, 1974 concert in Charlotte. Wayne lived in the mountains then, and drove to the city to stand in line when the tickets went on sale. I was at the other end of the state, going to college in Wilmington. I liked Dylan OK, but was a bigger fan of The Band. I knew all the words and guitar to “The Weight,” “Up on Cripple Creek,” “The Shape I’m In.” I wanted to go to that concert with someone who I knew would enjoy it every bit as much as me. Also someone who had a reliable car and could drive. I was seeing a girl, but that wasn’t going well and I decided she wasn’t worthy. So I asked around, and everybody I talked to pointed me to Dave, who they called “Fish” back then–a renowned connoisseur of concerts who also happened to have a beat-up Volkswagen Beetle with a hole in the floor on the passenger side so big you could see the road underneath. I didn’t pop the question right away. Dave–Fish–had stellar references, but I scouted him out anyway, just to be sure. Invited him to play ping pong, shoot pool, hit the basketball court for one-on-one. Get stoned and rock out to ZZ Top’s new album “Tres Hombres.” We clicked right away–both vegetarians, both lapsed Methodists, both hippies, both refugees from small Southern towns. We drove to Dave’s home town an hour away where I met his parents, Pauline and Dick, and Pauline loaded us up with vegetables from her backyard garden.

Dave and I got to Charlotte ten hours early the day of the concert with nothing to do and no money to do it with. We didn’t have any pot, sat in the worst seats in the coliseum, and were as blissed-out happy as if Dylan and The Band had just shown up at Dave’s house in Wilmington to jam for us and hang out. We even had a brief encounter with Bill Graham, the legendary concert promoter.

Wayne and his girlfriend were there, too, though they had floor seats right up front near the stage. They found us when the concert ended, stuck to our seats a good hour after the last encore, still soaking in the music, until the clean-up crew kicked us out. It must have been well past midnight by then, and we had a 200-mile drive ahead of us back to Wilmington. I was freezing from the winter air that blew in through the hole in the floor, but still managed to fall asleep while Dave, who always seemed to be taking care of me one way or another, drove the whole way home.

***

At the visa office one day, Dave ran into a Danish couple we had met in Bharatpur a few days before the accident. He asked if they had time to visit me in the hospital. The guy had a guitar, and Dave hoped if they came and played some tunes it might lift my spirits. They said sure, and spent a couple of hours with us at East-West making music and hanging out. I asked if I could borrow the guitar, and managed to fumble my way in three-quarter time through John Prine’s “Christmas in Prison,” a country-folk waltz I’d always loved. My voice cracked as I sang the refrain: “Wait awhile eternity/Old Mother Nature’s got nothing on me.” Before they left, the Danish couple offered me a marijuana brownie, which didn’t look like much, just a couple of bites. I washed it down with a big glass of Nestle’s Quik and spent the next twelve hours so stoned I was practically catatonic. It was New Year’s Day, 1977.

The nurses got so worried they kept coming in to check my vital signs, but then the munchies set in and I cleaned out a jar of Skippy. There were Ritz cracker crumbs all over the place.

A few days later, Dr. Chawla gave us the green light to fly back to the States–with a warning. “There remains infection,” he said. “And the pneumonia. But of most concern is you are continuing to have fluid collecting around the liver, suggesting you have not healed from the original injury. There is little more we can do for you here. You should prepare yourself for more surgery which will be necessary when you have returned to America.”

***

I spent the last few days in India in denial. I had been sufficiently changed by all I had seen and experienced, the people I’d met, the accident and the operations. Enough for now. I didn’t need anything else to happen. No more complications. I would be back in America soon. They fixed things in America. They would make me whole, make me well again there. When I broke my arm playing football, when Wayne broke his collarbone slipping on a rug, when they took my tonsils out, and my appendix, when we got the mumps, when Wayne had his poison ivy scare, when Dad had a nervous breakdown not long after I graduated from high school–they knew how to fix us. They weren’t able to fix our baby sister, but that was years ago, before they knew about incompatible blood types, Mom’s Rh negative and the baby’s Rh positive. Mom lost her infant daughter, but the next one, also a daughter, who they also named Johanna, survived. So in a way, they fixed that, too.

I dragged myself back up the stone stairs to the cold shower and forced myself under the trickle of water where I cried because it hurt, but I still stayed and scrubbed until I was red and raw, careful to avoid my wounds. It felt good to be clean, even when I had to put back on the same soiled clothes.

I fantasized about the reunion with my family. Maybe they’d still have the Christmas tree decorated in the living room, and they’d set me up on the sofa bed where I’d feel safe and warm, bathed in the soft glow of colored lights. I’d lie around for a few days, a week, see a doctor, pet Suzy, our Beagle-Basset who used to sleep on the bed with me and maybe would again, just to keep me company. I’d be miraculously cured. I’d return to Tallahassee, and Robin, who must have heard about the accident by now, must be worried sick, must miss me terribly.

We flew out of New Delhi January 6, five weeks after the accident. Dave made me walk from the taxi, through the airport, past customs, across the tarmac, up the steep boarding stairs onto the plane. He explained, “They won’t let you on if they think something’s wrong.” I was gasping for breath, looking for any reason to pause, to stop altogether, afraid I wouldn’t make it without the frequent, presumably surreptitious rests, too focused on myself to see how hard this was on Dave, who was having to say goodbye to India and it was breaking his heart.

***

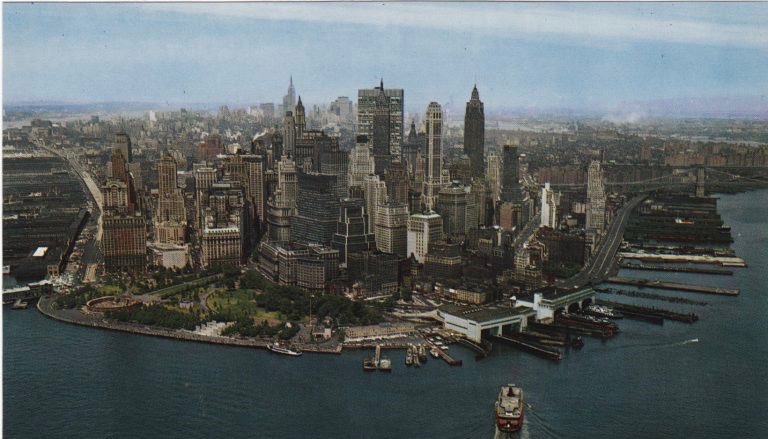

We were 25 hours flying from New Delhi to New York. There were stops–Dubai or Abu Dhabi or Qatar or Bahrain, one of those, and another in Frankfurt–but we never had to get off the plane, thank god, as I felt myself getting weaker as the flights dragged on. I wished I could lie down. Just sitting felt hard, felt like more than I could manage. David tried to get me to eat, to drink, but something about the arduous travelling, being out of the hospital, away from a bed for so long, had me retreating into a kind of shell. I pulled a blanket over my head. I was anxious every time I made my way down the aisle to the restroom, gripping the backs of people’s seats and holding on as if there was turbulence, even though the skies were clear the whole way. I was dizzy and had to sit on the toilet seat until my head cleared. Dave came looking for me and guided me back to my seat. By the time we landed at JFK I was dangerously dehydrated, barely able to stand, much less make my own way off the plane for our connecting flight to Tampa. But there was no wheelchair available, and Dave said I had to try. At least through Customs.

Once again he shouldered both of our backpacks and everything else there was to carry. We waited until the plane was clear before leaving ourselves. I managed to shuffle as far as the terminal. We had an hour to get through Customs and on to our connecting flight. We didn’t make it.

I got dizzy again and fell against a wall next to the women’s restroom, stumbled inside and collapsed on a toilet, doubled over with diarrhea while David ran for help. I managed to clean myself and stand long enough for Dave and an Air India clerk to guide me into an office where I could lie down. A doctor was summoned. Time stopped for an hour until the doctor, annoyed, harried, finally showed up, examined me, grilled David about how I ended up in this condition. He kept looking at his watch, wanting to send me off for tests, but Dave argued with him. We had a flight to Tampa, plans for me to be admitted to a hospital in Florida where my family lived. The doctor was angry for some reason, but caved.

“I’m going to let you go,” he said. “Not based on medical knowledge but on compassion, and I want everyone here to remember I said that.” The way he was so careful with phrasing made us think it was a liability thing, some sort of necessary disclaimer, except we were the only ones there.

Somebody brought a wheelchair, but we only got as far as Customs, where a burly agent pulled us to the side, wanted me to answer a long list of questions about where I’d been and what I’d done and what I was bringing into the country and what I had to declare. I struggled to speak. Dave tried to answer for me, but the Customs agent cut him off, said he was going to do a full body search.

I was too out of it to take in what he was saying, but David got pissed. “Can’t you see he’s sick? He needs medical attention. He doesn’t have any drugs.” They went back and forth as I drifted in and out of consciousness again, couldn’t hold myself up, started sliding out of the wheelchair.

Dave caught me before I hit the floor, but just barely. The Customs gave up on the body search and helped me back into the chair. They wheeled me to the room I had been in before, laid me down on a conference table, tucked a blanket under my head, and called the doctor to come back. I was agitated, talking more nonsense.

Dave did his best to calm me down, but when the doctor returned, we were separated–Dave taken away for more grilling by Customs, me carted off to an ambulance and taken to a hospital in Queens. I was vaguely aware of the EMTs cursing in their frustrated attempts to find a vein so they could start me on a fluid IV, then cursing some more because some asshole was tailgating us, even though the emergency lights and siren were on, must be some blood-sucking lawyer, fucking ambulance-chaser, thinking they got a live one here.

Dave was stuck for another hour at Customs–grilled, searched, questioned again, finally let through and given the address for a nearby clinic where I was supposed to have been taken, only I wasn’t there, and he used up most of the handful of dollars he had on him, taking a taxi to find that out. Phone calls were made back to the airport. The clinic receptionist was put on hold. Transferred. Transferred some more. Nobody knew anything. Dave was exhausted, frantic, ready to explode, already hating being back in America. He called it the Combine—bureaucratic, corporate, faceless, rigid. Took the phone, finally got hold of somebody who knew something. Was redirected to Queens General Hospital. Took another taxi. Spent the last of his American dollars to get there, only the driver didn’t know the way and they had to double back to the clinic for directions.

***

The EMTs finally managed to get the IV started, just in time to roll me into the ER at Queens. I was taken to an open ward on an upper floor with dozens of beds, no privacy curtains, busy nurses and aides scurrying from patient to patient, ignoring me even when the needle slipped out of the vein the EMTs had such a hard time finding in the ambulance. The IV fluid infiltrated the surrounding tissue, and my arm swelled painfully until I was ready to pull out the needle myself, and that’s when Dave showed up on the crazy, busy ward and saw what was going on and stormed off to grab somebody to help.

I was stuck in Queens hospital for the next three days. Dave found a cheap room nearby. Hot shower. Broken telephone. Sirens all night. Neon skyline. Thin walls. Fighting next door. Street pizza. Short walk to the hospital. Long taxi ride to exchange rupees for dollars. I was rehydrated, eating a little, feeling good enough to travel, so close to being home that I felt a level of desperation to get there that I hadn’t experienced before, maybe because I’d managed to suppress it, or maybe because I had been so far away in India, and so sick for so much of the time, that being home, being back in America–back with my family–was more of a dream than something that might actually happen. The complications at East-West Medical Center, each one eclipsing the crisis that preceded it, must have contributed to that feeling. But now, in New York, a short flight away–if we could only get the fuck out of Queens–the separation felt almost physically painful. No doctor would sign discharge papers for fear that they’d be liable if I died on the flight to Florida. And if I wasn’t officially discharged, my dad’s insurance wouldn’t cover any part of the bill. It was policy. Catch-22.

And yet the ward I was on at Queens Hospital in some ways—in many ways—wasn’t so different from the hospital in Alwar. For the first few days and nights, I slept, maybe sedated, maybe just past the point of exhaustion from the interminable flight and passing out at the airport. I’d been catheterized when they brought me in, but then, once they removed the catheter, had to make my dizzy way alone to the toilet at the far end of the ward, which seemed to be the size of a football field. I lurched from bed frame to bed frame, mumbling apologies along the way, though the other patients didn’t notice, or were too out of it themselves to care. Nurses came by occasionally, but rarely stopped at my bed. There didn’t seem to be any way to summon them when I woke up disoriented, panicked, lost in that strange, dark, cavernous room.

There were plenty of unemptied bedpans lying around, but fortunately no rats. And the toilets were relatively clean. No families camped out around their loved ones, so there was no food except for the plastic-wrapped meals they served three times a day that were always cold and never vegetarian. At least all the beds had mattresses.

One night after Dave went back to his crummy hotel, I made my way to the TV room and sat next to a guy in a wheelchair. I’d managed to put my worried mind on autopilot, trying not to think about the Combine, my wasted condition, more surgery to come, more scars. We watched a Knicks game. The guy in the wheelchair–he said his name was Gus–told me he’d just gotten out of prison, hadn’t had anywhere to go, slept in an abandoned car for a week. It snowed. Snowed some more. Snowed a lot. He got frostbite. By the time they found him, his feet had turned black. They had to cut off his shoes, then his feet. Gus lifted the bandaged stumps that were what was left of his legs, and he said, “Fuck it. They gotta take care of me now.”

An arrangement was finally made. If I could walk out of the hospital on my own, and if I could convince the airline to let me on the plane, and if I could survive the three-hour flight to Florida, they’d give me a retroactive discharge, which we didn’t know was a thing. An old friend drove down from Connecticut in his truck to give us a ride to the airport. Dave railed some more about the Combine and said he wished he was still in India.