“To forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”

By Steve Watkins

I recently finished work on a historical novel for Scholastic Press titled Stolen by Night which is scheduled for publication in Fall 2023. It’s the story of teenagers in the Resistance in Occupied Paris during World War II, many of whom, after their capture, were “disappeared” in Hitler’s “Night and Fog” program, Nacht und Nebel. Most of the NN prisoners were sent to Konzentrationslager Natzweiler-Struthof, the only Nazi-run concentration camp on what is now French soil, in the Vosges Mountains of Alsace-Lorraine. Tens of thousands were killed there. Few survived.

I read numerous books and articles in my research, most notably Ronald Rosbottom’s When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944; Boris Pahor’s Natzweiler memoir Necropolis; Nikolaus Wachsmann’s KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps; Charlotte Delbo’s Auschwitz and After; Jacques Lusseyran’s And There Was Light.

And then there was the document which I’ve posted below, “Investigation Report on the Life in a German Extermination Camp (KZ Natzweiler) and the Atrocities Committed There, 1941-1944,” compiled by a three-man investigative team led by British Army Captain Yuri “Yurka” Galitzine. The military investigators were among the first to enter the camp after it was liberated late in 1944—too late for most of the prisoners, who were either executed on the eve of liberation, or relocated to other concentration camps deep inside Germany. Moving quickly, Galitzine and his men were able to locate a mountain of camp records and dozens of witnesses: a handful of prisoners remaining in the camp, townspeople, contractors, guards, and four of only a small number of prisoners who had managed to escape from Natzweiler. Their investigation produced one of the first on-site reports of the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps.

Shaken by the account, and curious about the name of the principal investigator, I spent a considerable amount of time learning what I could about about Galitzine, though nothing about him is included in Stolen By Night. His name, as I soon discovered, was a somewhat Anglicized version of Golitsyn, one of the most prominent noble families in what was once Tzarist Russia. Yuri Galitzine, as it turned out, was actually Prince Yuri Galitzine, and as a boy, like many in the White Russian nobility, he fled from his home during the Russian Revolution, ending up in England where he continued his young life, growing up in a world of wealth and privilege.

He also grew up to be, for a time, an anti-Semite and Nazi sympathizer in the years leading up to the Second World War, something we know from records of the notorious Right Club, a secret organization of right-wing extremists that included members of Parliament, military officers, and British royalty, most famous of whom were the Duke of Wellington, the German spy Anna Wolkoff, and William Joyce, who later became the Nazi propagandist known as Lord Haw-Haw.

Many in The Right Club ended up in prison for treasonous activities. Galitzine was one of the few whose story followed a redemptive arc, as his experiences—serving in the military, losing friends in battle, and exposing Nazi atrocities at Natzweiler and other camps—appear to have changed him. After the war, he devoted himself to advocating for the creation of an “International Bureau of Information” to ensure an effective response in the future to the sort of propaganda that fueled Hitler’s rise to power, and without which, he believed, the Third Reich might never have come into existence.

***

It’s impossible not to compare Yuri Galitzine’s story with the life of Hauptsturmführer Josef Kramer, who served as kommandant of KL-Natzweiler-Struthof for three years, from April 1941 to May 1943, after which he was appointed kommandant at the notorious Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where he earned the nickname “The Beast of Belsen.” Among the many atrocities for which Kramer was responsible—documented by Galitzine in his report—were the murders of 87 Jewish prisoners, brought to Natzweiler to be studied, then killed, then included as specimens in the Jewish skeleton collection of Anatomy Professor August Hirt at the Reich University in Strasbourg. At his trial after the war—for Crimes Against Humanity—Kramer confessed to the murders.

One evening, about nine o-clock, I led about fifteen women to the gas chamber. I told them they were going to be “disinfected.” With the help of some of the SS guards, I got them completely undressed and pushed them into the gas chamber. As soon as I locked the door, they started to scream. Once the door was locked, I placed a fixed quantity of the hydrocyanic salts given to me by Professor Hirt in a funnel attached below and to the right of the peep-hole. I illuminated the chamber’s interior by means of a switch located near the funnel…. The women continued to breathe for half a minute and then fell to the floor. I turned on the ventilation, and when I opened the door they were lying dead on the ground. They had lost control of their bowels.

I entrusted two SS guards with placing the corpses in a delivery van, on the next morning at about half past five, in order to have them taken to the Institute of Anatomy as Professor Hirt had asked. A few days later, under the same conditions as described above, I again brought a number of women to the gas chamber, and they were asphyxiated by the same procedure. A few more days after that, some fifty men, perhaps fifty-five, were taken to the gas chamber on my orders, on two or three occasions, and killed there by means of the same salts that Hirt had given me. I do not know what Hirt was going to do with the corpses of these prisoners, assassinated at Struthof on his instructions. I did not think it appropriate to ask him.

I felt no emotion while accomplishing these tasks, because I had received an order to execute the prisoners in the manner that I have described to you. That is simply how I was brought up.

***

I was only able to to find the Natzweiler report online as a PDF of Yuri Galitzine’s original typescript, and I’ve worried about that—worried that because it may be difficult to locate, and difficult to read, it could in some ways become lost or forgotten, the way most things, even terrible things, fade from our collective memory. Which is one of the reasons I’ve reproduced it here, as a resource for other researchers, and for readers–a chronicle of the horrors of Natzweiler written in dispassionate, even bureaucratic language by perhaps the least likely of men. “For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear,” wrote Elie Wiesel in his Holocaust memoir Night. “[H]is duty is to bear witness for the dead and for the living. He has no right to deprive future generations of a past that belongs to our collective memory. To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive; to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”

***

INVESTIGATION REPORT ON THE LIFE IN A GERMAN EXTERMINATION CAMP (KZ NATZWEILER) AND THE ATROCITIES COMMITTED THERE. 1941-1944

To: Chief Liberated Areas Section PWD SHAEF (Political Warfare Division/Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force)

From: Capt. Yurka N. Galitzine

NOTE: This report is based on personal investigation and observation made during operations in the area in Dec 1944.

I. Origins of the camp.

In the spring of 1941 German geologists and mining engineers came to ROTHAU in ALSACE prospecting for red Alsatian granite to face the “Party” buildings in NUREMBURG. They conscripted the local civil engineer, M. Ernst KRENZER to help them in their task and made several excavations in the early spring. At last the stone was located in March 41 on an upper ledge of the mountain behind ROTHAU, very near the Alsatian skiing resort at the Hotel STRUTTHOF.

During the spring of 1941 the local firm of stone-masons and contractors, SADLER & Co of GRENDELBRUCH were conscripted to start working a quarry as a commercial proposition and at the same time to start a road up the mountain.

Suddenly without any warning one day in April several German military trucks brought 150 civilian prisoners up to the Hotel STRUTTHOF (closed some while before) where they were parked under guard and set to work. All the inhabitants of nearby farms and houses on the mountain were turned out and it became a restricted area. The first work done by the prisoners was the completion of the motor road on the mountain while some worked in the quarries. Both working parties were supervised by civilian foremen from STADLER & Co and were guarded by S.S. guards. These first prisoners were mostly German “anti-Nazis” and Russians.

The numbers of the prisoners gradually increased and apparently at the same time the plans of the Germans became greater enlarged in scope.

2. The building of the camp

The Germans started to build a camp on the summit of the Struthof hill. This camp which they finished at the outset of 1943 consisted of two halves—a wired-off area for the prisoners, and a military barracks for the S.S. guards.

The prisoners area was built in a clearing on an exposed slope of the mountain with a very beautiful view which was little compensated by the bitter cold climate at that altitude (3000 meters). It consisted of 15 barrack huts built in three rows of five on “terraces”, cut out of the mountain side. The huts were designed to hold 200 persons and were equipped with bunks, stoves, electric light. W.C.s, wash basins, etc. However, as will be explained, it was the regime rather than the surroundings which provided the horror of the place. Also in this compound were a solitary confinement hut, a disinfestation hut and a crematorium. The whole compound was surrounded by a double wire fence with guard posts at intervals and through the wires ran a high voltage current.

The barrack huts of the S.S. men were similar to those of the prisoners, while the camp commandant lived in a comfortable brick house which also served as a camp office just outside the prison enclosure.

3. The quarry.

The quarry is situated on the opposite slope of the hill and is also surrounded by a wire fence with guard posts and joined to the camp by a road fenced on either side with barbed wire.

The quarry was developed through the years 1941-43 by which time enough stone had been extracted. Then the Germans decided to use the ledge formed by the excavations as a factory site, and a repair and recondition works for Junkers aircraft motors was set up. This was enlarged and developed until in 1944, it was decided to try and install the whole factory underground, so gangs of prisoners were set to work digging tunnels in the side of the mountain for this purpose. However this work was interrupted by the arrival of the Allies.

4. Organization of Slave Labour.

As the camp began to fill up the plan of the Nazis unfolded. This camp was to be a distributing and restocking center for slave labour. The records found in the camp show that when sufficient stone had been quarried for NUREMBURG they decided to use the camp as a holding center for the distribution of prisoners to any government enterprise which needed manual labour with the idea of “working the prisoners to death”. When a batch were so exhausted that they could work no more or had succumbed to some disease as “T.B” or typhus, they were sent back to STRUTTHOF to be put out of their misery and a new batch was sent up to replace them. The areas “serviced” by the camp appear to have been ALSACE, BADE, HESSE and occasionally LORAINE.

Although the camp at STRUTTHOF itself never held more than 6000-7,000 prisoners at a time, many thousands passed through its hands. On the work book of the camp in 1944 there were some 31 places listed involving at one moment 24,000 persons.

***

5. Identity of the prisoners.

a. Nationality

Most of the original 150 who arrived in 1941 were German political prisoners and Russians, some of whom were soldiers and some civilians. As time went by more and more Russians came. Luxemburgers too (including the brother of the husband of the Grand Duchess, the Minister of State and other Luxemburg notables), also Dutch, Belgians, Norwegians and Czechs were amongst the early batches. Later came Greek, Italian and Yugoslav partisans and it was only in early 1942 that the first French prisoners were brought in. The first batch of these were mainly cures and gendarmes. There were never many French in the camp, though among the few there were reported to be seven generals, one of whom, Gen. FRERE the ex-military governor of STRASBOURG died (of “weakness”) in Aug 1944 only three days before an attempt to rescue him was scheduled to be made. The French prisoners were not allowed to mix with the others.

The first Poles to be brought in were a whole village from near LUBLIN who arrived one night in 1942. Many of them were suffering from typhus, a disease which had never touched the camp before.

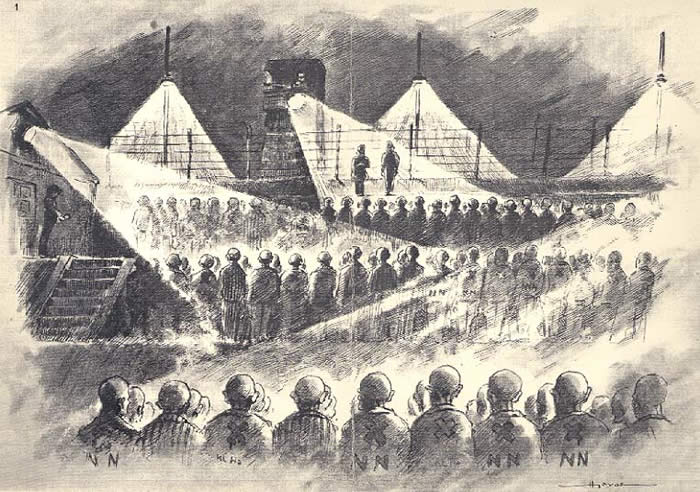

It is reported that there were two Englishmen in the camp — one officer and one professor. The latter left some drawings of his fellow prisoners which he managed to smuggle to one of STADLER’S foremen, M. NICOLE. These drawings bear the signature — “B.J. STONEHOUSE.”

***

It is also reported that five American airmen captured after a raid on STRASBOURG were interned in this camp. No confirmation of this has been obtained.

Very few women passed through this camp. Of those who did most were killed almost immediately. The total probably did not exceed 150, of these most were Polish, Jewish and French.

b. Classification of prisoners.

i. Prisoners were classified under one of eight groups and each group had its distinctive sign and colour, which was worn on the prisoners clothing. Underneath the sign was the prisoners number on a white tape. All articles of clothing had to bear the sign and number. The group signs were as follows: Felon: Green. Criminal: Green. Political (Military): Red. Homosexuals: Blue. Political: Red. Forced-labor dodgers: Black. ‘Bibelforgers’(conscientious objectors and religious): violet. Jews: Yellow.

***

ii. Certain prisoners who were considered more dangerous or who had attempted to escape were designated “N.N.” prisoners, the N.N. standing for Nacht und Nebel (Night and Fog). These prisoners also wore a yellow patch with three black circles over their heart. They could be shot for the slightest misdemeanor and were not allowed any mail or communication with other persons. There were many Norwegians in this category.

6. Camp Regime.

a. Administration

The prisoners were divided into ‘blocks’, each one corresponding to a barrack-hut. In these ‘blocks’ prisoners were appointed and made responsible for the general administration and discipline. These senior prisoners (known as “Kapos”) were usually German and chosen from among the common criminals (e.g. murderers) or sexual perverts (e.g. sadists); for some time the chief prisoner was a sexual pervert from HAMBURG. They had full disciplinary authority over the other prisoners in their block, and were allowed to beat or strike fellow prisoners. In fact, in 1943 when things were at their worst, if a Kapo were to kill another prisoner it would have been completely overlooked.

A story of an incident which happened in 1943 well illustrates the attitude of the Kapos. Some prisoners were working in the quarry and a fall of rock caught and crushed the leg of a Russian prisoner. He took the accident very bravely, but was in tremendous pain. The German doctor appeared, applied a tourniquet of dirty rags and sawed off the crushed foot. He then poured a bottle neat iodine onto the raw wound, laughing as the prisoner lost consciousness with the pain. The Russian was carried back to his hut where he lay for several days before he died. But during the time he lay there he used to moan and cry with pain as the leg festered. So every so often the Kapo would walk over and thrash the dying man with a heavy stick telling him to shut up.

Each block had an SS officer over it, but the ordinary other ranks of the guard were kept strictly outside the compound and were not allowed to talk to prisoners. Only the duty officers, NCOs and work details of SS for the crematorium, prison, etc. were allowed in.

Each barrack hut was designed to hold about 200 prisoners; in fact they had over 600 crammed in. There were three in every narrow bunk. Others slept in the W.C.s and the corridors. The prisoners tried to keep warm by each picking enough twigs to light the fires in their huts, as the Germans provided no coal or wood or paper, and they considered it was waste of working time when wood was collected.

b. Daily Routine.

0400 hrs Reveille. Breakfast of a bowl of thin watery soup.

0500 hrs March to work.

1200 hrs Break for a meal of soup with a small bit of bread

1300 hrs Back to work.

1800 hrs Finish work. Allowed an hour to go to the dispensary. Every one into compound.

1900 hrs Dispensary closes. Soup & a bit of bread.

2000 hrs All prisoners confined to their huts.

c. Food.

The undernournishment was terrible. All the solid food which the prisoners were given was a small crust of bread and they had a bowl of thin “soup” three times a day. All the utensils they were allowed was a wooden spoon.

Occasionally the SS guards would go out into the forest and shoot a deer or a wild boar. Then they sell through the Blockleiters the portions which they themselves did not want (usually the entrails etc.) at 15 to 20 marks a lb. As the ordinary prisoners were only allowed to receive 50 pfennigs a month and the Kapos 1 mk. 50 pfg, it meant that they squeezed the small amount of savings the prisoners had. A canteen was available where cigarettes were sold once a month.

Many prisoners got swollen or distended stomachs from undernournishment, all became very weak and succumbed to dysentery, constipation and many other illnesses. The Russians seemed the worse hit, and pathetic sights are recounted by STADLER employees of Russians eating grass and even dung. Some used to hunt for worms in the mud of a little spring in the quarry. A pathetic description was given to me of a little Lorrainer who died of hunger in the quarry in the summer of 1943. He was left to die and no one was allowed near him.

d. Health.

One of the barrack-huts was set aside as a dispensary and laboratory, and in the crematorium there was a doctor’s office and a room for autopsies with an examination slab. There was also a hut for the disinfestation of dead bodies and clothes.

The dispensary was only open for prisoners between 1800 hrs and 1900 hrs and naturally there was always a long queue. So that if an unfortunate did not get in on time he had to wait till the next day. Bandages were scarce and those available were made of paper. One prisoner was seen to be working in the quarry with an open wound in his back as big as a man’s fist. It was a festering boil, which he had stuffed with dirty rags. A kind foreman (M. NICOLE)from STADLER’s managed to smuggle enough medicaments to him to cleanse it and heal it.

Typhus was brought in by the first Poles from Lublin, and it soon spread. In the end five barrack-huts were isolated for typhus cases. Many prisoners got stomach or other internal troubles or weak hearts. In winter many prisoners were paralysed with cold as the climate was terrible. A lot died from swollen limbs due to the cold.

Prisoners were not allowed to go to the lavatory during working hours. This also had a terrible effect on their health.

7. The Camp Staff.

The German officers and NCOs were all without exception incredibly brutal. They were all drawn from the ranks of the SS. They were allowed to hit, kill or torture at will during the first years until 1944 when even their right to strike was officially withdrawn though this did not deter from doing so. The Kapos had also been stopped from striking their fellow prisoners.

The rank and file of the camp guards were usually SS though occasionally Wehrmacht. It should be noted that prisoners claimed that the latter were always more cruel. At the beginning all the guards were equally cruel, but in later years were were many Volksdeutsche impressed into the SS who were much more tolerant. They were usually treated badly by the regular SS men and not trusted.

No one was allowed to talk about the camp. The German guards themselves never even discussed it amongst themselves and all civilian employees, such as the quarry foremen, signed a paper and swore not to talk.

***

8. Deaths and Torture.

a. Torture. Little authentic evidence beyond the statement at Annexure C is available. There are two rooms in the crematorium about which graphic descriptions are given by the present FFI guards at the camp. These men know nothing of the true story as even the four prisoners who escaped from the camp and a captured SS guard could not give much details as very few men tortured ever came out alive. All that could be confirmed were the cries and shouts which could be heard all over the camp coming from these two rooms. b. Shooting. The majority of the deaths were caused by shooting. Prisoners who were sentenced to death were normally taken up to the sandpit between the camp and the quarry and shot there. The first death occurred on 24 May 1941 when a party of prisoners were working on the new motor road. Two prisoners broke ranks and tried to gain the cover of the forest nearby. The SS guards opened and hit one in the stomach, leaving him to die while they pursued the other. He lay there from midday when the incident occurred till five o’clock when the other prisoner was finally caught on the other side of the valley. They were Germans presumably anti-Nazis and records that the one was left lying on the ground pitifully crying “Mutter, Mutter.” was called Albert Alfred BERGMAN (born 1896) and the cause of his death is gen as “Weak heart and dysentery”. They were both shot. During the time that the search was going on the other prisoners were made to lie face down in the mud with their arms and legs spread-eagled. A favored trick of the SS NCOs (especially Fuchs of Kehl) was to throw a stick or cap outside the line of guards where work was going on. If the prisoner crossed the line he was shot for breaking bounds and if he did not go he was shot for disobeying an order. There was a Standing Order offering three days furlough to any SS guard who shot a prisoner. There were many volunteers for this work as a result. Early in 43 the first Alsatians were brought to the camp. They were 13 young Strasbourg patriots. Eleven of them were taken up to the sand pit and tied together in small groups. Then SS NCO Fuchs with a squad of Croat SS men had target practice on their bodies, shooting them in various limbs before Fuchs himself went to deliver the “coup de grace”. The other two left over were made to carry the bodies of their comrades down to the crematorium where they themselves were shot in the nape of the neck on the steps. One day three women “spies” were brought up by car to the camp and shot in the sandpit. They are described as being one Englishwoman and two French women, and all were ‘well dr3essed’. c. Hangings. When prisoners attempted to escape or some such breach against the general discipline of the camp, a public example was often made by hanging the unfortunate in front of all the other prisoners. Volunteers were always called on from amongst the latter to take away the stool under the victim’s feet. But they were never forthcoming and it ended by two being detailed. A pathetic eye-witnesses story is told about a little Pole who was sentenced to be hung. The rope with which he was to be executed was too long and he merely fell to the ground with the halter around his neck crying “Warum. Warum.” So they shortened the rope and tried again. d. Gas Chamber. A special gas chamber for experimenting in lethal was gases was built down at the old STRUTTHOF hotel early 43. There was a little glass panel at the side to enable doctors to watch victims’ reactions and a hole in the door for the insertion of a gas cartridge. Each prisoner was fed well a week before being gassed. A special card was kept on the intended victim. Sweets and cakes were given on the day of the experiment. Some even got out alive when the gas failed to work, but they always died in some other way later. The doctors tried to ‘revive’ patients by injections as antidotes to the gas. Most of the victims in the gas chamber were women, some 150 were killed in this way including 50 Polish women who were put in at once no one coming out alive. They were stripped first, raped and then crammed into the small chamber (about 12 ft by 12 ft). In the crematorium there is another room where prisoners were also killed by carbon dioxide gas from the furnace of the crematorium. In here most Jewish victims were killed. e. Crematorium. In the beginning of the camp when deaths were less frequent a lorry left the camp twice a week for STRASBOURG where the bodies were burnt in the town crematorium. But after a while the town authorities objected as the numbers increased, and a small crematorium, capable of burning 4 bodies a day, was built opposite the STRUTTHOF hotel. This was also too slow and often the coffins could be seen piled high by the side of the road by visitors to the camp. So that at the end of 1942 the camp authorities built a fine crematorium within the prisoners’ compound. The crematorium is the most interesting and the most horrible building in the camp. There are a flight of steps leading down to a small room where many victims were probably shot as they were forced down the steps. Here in this room the bodies were stacked and fed into a lift which took them up into the furnace room. Here the operator used to put as many as three bodies at a time into the furnace. Outside lines a pile of coffins used to carry the dead to the dead sandpit or the distant gas chamber. Inside there can be seen the “pin-up pictures’ of the man who tended the furnace, the slab on which the autopsies were performed. It has been rumoured that vivisection was practiced here but no proof is forthcoming. In another room there is a store of little earthenware urns. It was into these that the ashes of burnt prisoners were put, when their families were lucky enough to be able to ask for their remains. They had to pay 75 marks for this privilege. For those who were not ‘bought’ back by their families there was a dump outside the hut into which their ashes were thrown along with all the camp rubbish. This dump was incidentally also the camp sewer. Seepage eventually occurred and polluted the water supply of Rothau down in the valley 9 kms below. Cremation was known to the local French people as ‘passer par la cheminee’. Here only specially picked squads of SS men and condemned prisoners were allowed to penetrate so little reliable evidence can be obtained what happened inside. On the evidence of an SS guard, however, it is known that on 1, 2, and 3 Sept 1944 the last days before the evacuation, 200 Frenchmen and 50 Frenchwomen were brought in and killed. No identity papers of the victims were retained and the floor of the little room below the furnace was said to have been 10 to 15 cms deep in blood according to the evidence of the SS guard who had to clean it out. f. Medical Experiments. The prisoners were used unhesitatingly as human guinea pigs. They were often given injections to test their reactions to certain new serums, and they sometimes died from these. There are stories that vivisection was practiced by the camp doctors on the ‘autopsy’ table in the crematorium, but this can not be confirmed. 120 bodies of prisoners have been discovered in the Anatomical Institute of the Strasbourg Hospital. Apparently acting on a telephone call from Prof. JUNG, head of the Institute, the Camp Comdt sent two lorry-loads at 0500 hours next morning of bodies, naked and still warm when they arrived. They appeared to be “still alive” having been injected with serum. Some were women. The bodies found were preserved in alcohol in jars, some being already cut up. The prison numbers of all the bodies are available which will permit identification. g. Statistics. In the early days the Germans registered the deaths of their victims at the Mairie of NATZWEILER, the nearest village. Here too can be found the signatures of the doctors responsible. Most of the causes of death are given as “weak heart”, “heart failure”, “dysentery”, or “typhus”. Only two cases are noted as executed. *** It is improbable that all deaths were listed during the period. In Feb 43 the new crematorium was finished and all registration of deaths was done at the camp. It is estimated that between 5000 and 6000 were killed here, although French reports (quite unsubstantiated) put the figure as high as 11,000. 8. Escape. There are only two known attempts at escape from this camp which have succeeded. The first was in 1941 when the son of a Russian general aided by three of his compatriots seized a German staff car standing outside the STRUFFHOF hotel and got away. Three of the escapees were recaptured and shot. But the Russian general’s son is reputed to have got to Switzerland. During the evacuation of the camp in Sept 44, as the last lorry was leaving the camp, it broke down on the hill outside. With the aid of the local FFI *** four Luxemburgers managed to escape. Their statement is attached at Annexure C. They have since returned to LUXEMBOURG. The Germans were very strict during attempts at escape. All prisoners were stood to attention until the man was recaptured, or working parties were made to lie flat with their face on the ground, immobile. In fog the SS guards were most afraid and herded the prisoners together and put them back in their huts. 9. Evacuation. The camp was evacuated on 4 Sept 44 two months before the arrival of Allied troops and all the prisoners except a cleaning up party of about 40 were sent back across the Rhine. The factory was kept in operation by the use of local hired civilian labour. 10. A Prisoner’s Appreciation. A German Communist who had done ten years in various concentration camps told M. NICOLE, a foreman that “I preferred DACHAU to this. It is larger so that you can get lost easier; it is better organized and the climate is better.” *** [What follows in the report are “Annexure A: German War Criminals in the Struthof affair,” and “Annexure B: Witnesses for Crimes committed at Struthof Camp.” “Annexure C, below, is the statement/report given by the four members of the Luxemburg Resistance Movement who escaped from the camp.] *** 1. Gas Poisonings. On 2 Aug. 1943, 59 men and 29 Jewish girls were transferred from the Ravensburg [SIC] camp to the KZ Natzweiler. Then on 11 Aug., after 8 days of medical examination, 15 women were led to the gas chamber. Upon their death, they were taken to Strasbourg for post-mortem examination. On 13 Aug. the remaining women were killed in the same manner. The first 30 men were killed in this fashion on 17 Aug., the remainder 2 days later. One of the girls managed to tear herself loose and jumped over a small wall. She was shot dead on the spot. *** The following morning the undersigned observed blood traces leading from the gas chamber to the loading ramp. To supplement the aforesaid, may it be added that gas experiments were made from time to time with prisoners, to experiment with new gases, in the course of which most of them died. *** The gas chamber is located outside the camp, in an annex of the Hotel Struthof. 2. Mutiny in the Quarry: (June 43) 100 Russians and Poles were alleged to have had the intention to prepare a mass escape by overpowering the guards, then seize their weapons and make a get-away. The trial began in the evening toward 9 o’clock, when the alleged ring-leaders were brought up for interrogation; since the investigation chamber was separate from the sleeping quarters by only a thin wooden partition, the other prisoners were able to follow the whole interrogation. In order to extract confessions from the prisoners, their hands were chained to their backs, and they were strung to the ceiling by their tied hands. In the course of this, the SS-men participating in the interrogation also whipped them. After half an hour was up every single one (of the prisoners) was willing to confess everything the SS-men wanted to know, just to be relieved from their tortures. A few among them lost their minds through their tortures, and began to sing. About 30 were subjected to this torture. The SS-men conducting the interrogation were given wine and spirits to whip-up their fury still further, and afterwards, knew no restraints. The prisoners in the next room could not sleep during the night because of the continuous cries of pain of those being tortured. At reveille, the accused were taken away. Most of them had been tortured to such an extent that they could no longer walk, but had to be dragged. There were some among them whose faces were bruised so badly that they were beyond recognition. After four weeks, during which time they continued to have their hands tied to their backs and were exposed to the weather, those concerned were publicly hung, in the presence of all the prisoners. Those chained in this manner had remained chained at all times, and their hands were not free when they had to relieve themselves, or to eat and drink. The chains grew into their flesh, the upper arms were blue from the stopped blood, and had (so to speak) died off. The ones responsible for this act were:-- SS-Hauptsturmfuehrer Kramer SS-Oberscharfuehrer Buttner SS-Hauptscharfuehrer Zeuss SS-Oberscharfuehrer Nietsch SS-Unterscharfuehrer Ehrmantraut SS-Unterscharfuehrer Fuchs SS-Rottenfuehrer Ohler 3. Solitary Confinement: Before the organization of a cell system, all prisoners to be punished were locked up in one cell, 2 meters long and 1.50 meter wide, furnished with one wooden cot. Their hands were chained behind their backs. Food consisted of water and 350 grams of dried bread, and 1 liter of watery soup every three days. 4. French Prisoners: In the summer of 1943 the first shipment of French NN-prisoners arrived and it was intended to exterminate them without exception. On the first Sunday morning of their stay in the camp, they had to fall out in the pouring rain to carry stones from the commandant’s building into the camp, in double time, and in so doing they were beaten with sticks by the Blockfuehrers and chased by the dogs until they broke down, completely exhausted. They were then left to lie on the camp parade grounds until noon. Most of them were bleeding profusely from the dog-bites and the slashes of the sticks. The fifty men concerned were organized into a special work detail, and had to perform the heaviest types of labor in camp. Some of them were put into an extra detail which the prisoners called the “death detail.” After 14 days, only 30 of the 50 men were still alive. All of them had to work under the worst mistreatment, and were guarded by a chain of sentries. The detail leader permitted himself the sly joke of sending 2 or 3 prisoners through the sentry line with the order to fetch some stones. While doing so, they were shot down by the sentries. Detail Leader: SS-Unterscharfuehrer Fuchs. 5. Treatment of NN-prisoners: Admission to the infirmary was barred to these prisoners. We have seen their wounds which they bandaged with old rags. Those unable to work were dragged to their place of work and left to lie there in the sun or rain all day. They never received hot meals, because they were incapable of work. Their nourishments consisted only of bread. The treatment of the NN-prisoners was such that after a few weeks they were completely exhausted. The term NN-prisoners is applied to people who are guilty of an infraction committed in “Nacht und Nebel” (night and fog). These people were not allowed to received mail or personal packages. 6. Executions: Only the smallest number of executions were performed according to regulations. The prisoners were killed through a shot in the neck by the SS-men. *** The execution premium consisted of 2/10 liter “schnapps”, 300 grams of sausage, and 6 cigarettes. In this manner, by hanging and shooting in the neck, 92 women and approximately 300 men were killed during the night of 1st to 2nd Sept. 1944. The corpses were stacked up in a cellar, in which the blood was 20 cm. high. Since these prisoners were not included in the K.Z.N. list, their exact number cannot be stated. They are alleged to be a group of partisans who had been captured in the vicinity. *** During the months of July, August and in the beginning of September, executions by shooting and hanging were carried out almost daily. Only in the rarest cases were executions carried out in front of the prisoners. Then mostly were executions of prisoners who had intended to escape. In such cases they were hanged in the presence of the other prisoners, as an intimidation. The punishment of thrashing was often ordered for minor infractions. Prisoners were laid across a block, and then received 20 to 30 blows on the buttocks, executed with full force. There have been cases where a fugitive was recaptured. Then he received more than 100 slashings with a stick or whip so that his buttocks were so badly bruised that for weeks he could neither sit nor lie down. In the case of a thrashing, the whole camp had to assemble. When it was noticed that someone had escaped, the entire camp had to stand in the open until the fugitive had been caught. 7. Rations Issued: Much of the blame for the bad state of health of the prisoners can be ascribed to the fact that the food rations to which they were entitled, were subject to embezzlement. They were entitled to the following ration per day: 350 grams bread 25 grams margarine 15 grams meat scrap 50 grams jam (once a week) 20 grams sausage 50 grams cheese (once a week) Because of embezzlement by those responsible for the provisions, prisoners did not receive the above ration allowances. *** Most of the time the noon-meal soup consisted of turnips with two to three unpeeled potatoes. ***

Steve Watkins, editor and co-founder of Pie & Chai, is the author of 12 books, a retired professor emeritus of American literature, a recovering yoga teacher, and the father of four remarkable daughters. He is also a tree steward with the urban reforestation organization Tree Fredericksburg and founder of Rappahannock Area Beaver Believers, a wildlife advocacy group, which you’re welcome to join on Facebook. His author website is stevewatkinsbooks.com.