Clear and Present

By Steve Watkins

The Fredericksburg [Virginia]School Board on Monday unanimously approved a new policy prohibiting the use of “personal communication devices” by students in school buildings during the school day. –FXBG Advance, July 2, 2024

***

Shortly into my first year teaching English and International Baccalaureate Lang & Lit at Mountain View High School in Stafford County, Virginia—the first day, actually—I knew I was going to have to do something about the cellphones. If a school shooter had blasted his way through the door to our classroom, the kids might have videoed first, posted on social media second, and only then looked around for somewhere to hide. And that’s IF they’d been able to pull their faces away from whatever was streaming on their iPhone screens to even notice. Not that I allowed them to be on their phones. They were just that good at sneaking them out, and that uncaring about my disapprobation and orders for them to put the damn things away already so we could get back to discussing the implications of the curious elliptical passage at the end of chapter two in The Great Gatsby. (A drunk Nick Carraway, the narrator, is standing in the bedroom of the photographer Mr. McKee, who is sitting on the bed in his underwear.)

I struggled through that first year—it was 2017-18; I’d gone back into teaching because we needed the health insurance—and I was clearly no match for the phones. Kids would sign out to go to the restroom and not come back for 20 minutes, if at all, meeting up with friends in other classes who they’d surreptitiously texted to set up their rendezvous for making out in stairwells, smoking and vaping in bathrooms, general wandering in the halls. Anything to avoid being in class. (Stuff at which I also excelled back the day, I should acknowledge, though without the aid of electronic communication.)

Cellphones were a big help to my students for cheating, too, of course, so much so that I stopped doing teacherly things like reading quizzes and grammar skills assignments, because what was the point? They plagiarized research papers and essays easily enough online as well, though those tended to be laptop jobs—made all the easier these days with AI, which during my three years at Mountain View was still just over the horizon. But we knew it was coming.

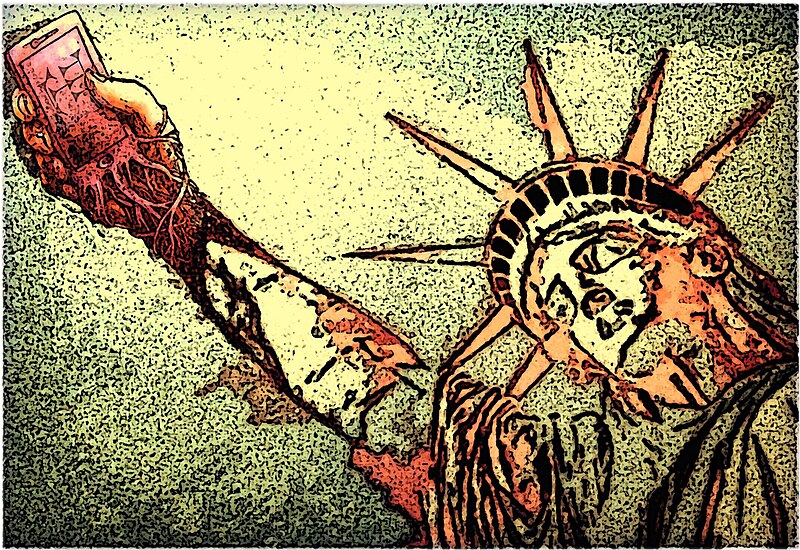

The cellphones, though, were a clear and present danger. Not that I blamed the kids. They were just doing what they’d been trained so well to do since childhood. Sometimes at the end of class, when they were gathered at the door in a silent scrum—ostensibly waiting for the bell to ring but really just free to pull out their phones with impunity—I would go around to check out the various internet amazements to which they were so breathlessly drawn. A few would be madly texting, but most were nose-to-the-screen into videos of various stripes, all of which were such drivel that it would injure my brain describing them to you. And that was before TikTok.

I thought of those kids recently while reading Alexandra Fuller’s memoir Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight, about her 1970s childhood in Zimbabwe—and in particular this brief passage in which a young Alexandra and her older sister are left for a few hours in the semi-arid bush, miles from anything and anyone and anywhere, waiting for their father to come back from hunting an impala:

I make a cake out of dirt, leaves, bark, and water. I decorate it with stones and sticks, sprinkling it with shiny white sand. I put it on a rock to bake in the dying light of the sun. Then I am bored. I lie on my stomach in the flat dirt, poking pieces of grass into ant lion traps. I catch ants and drop them into the tiny funnel-shaped traps and watch the ant lions scurry up, minute claws waving, to catch the scrambling ants. I lie on my back and squint up at the sky, watching blue through the fronds of the ivory palm tree.

The passage describes a moment as dry as toast—and is worlds more interesting than the video cheese those poor high school lab rats so eagerly, even desperately, devoured while waiting for the bell.

Again, not that I blamed them. They were just doing what they’d been programmed to do.

***

I taught college for a long time, and the concept of “classroom management” wasn’t one I ever heard discussed there. Students who didn’t want to be in class could simply choose not to attend, and that was pretty much the end of it. They might take a participation grade hit, and some old-school members of the professoriate had attendance policies with penalties for no-shows, but it was still the students’ call whether to put in an appearance. In my high school classes, of course, kids weren’t given a choice—and weren’t shy about letting me know how unhappy they were about it. The first time a student called me an asshole was my second day of teaching. Not long after that, another teacher overheard a kid saying that he was going to follow me home and murder me, though she didn’t report it until she discovered him looking up my home address on a school computer.

Another difference was that when I left college teaching a dozen years ago, cellphones weren’t yet that big a concern. Fewer than half the college students had them back then, and among their high-school-aged siblings, the number was even smaller. (April 2010 headline in Fortune Magazine: “Survey: 31% of U.S. teens want iPhones. And 14% already own one….”) By the time I got to Mountain View, though, nine out of 10 kids were hooked up, and the cellphone epidemic had spiraled all out of control.

I read a number of studies about teen cellphone use, trying to get a handle on what I was dealing with, and soon had a folder full of evidence confirming empirically what most sentient beings had already deduced: Smartphones were wrecking young people’s lives. More specifically, according to one University of Virginia researcher back then, they were creating “ADHD-like symptoms” in users, diminishing happiness in social settings, eroding trust between strangers, and damaging connections between parents and kids. (I read another study that said 10%of people reported checking their phones during sex, though it wasn’t clear how many were teens, only 30% of whom say they have sex of any kind these days, a significant decline over the past couple of decades.)

Also alarming, and of particular relevance in the classroom, was a study I found comparing high-schoolers’ cognitive test results under three different conditions: when students had their iPhones in their pockets during testing; when students’ phones were close but not immediately accessible, perhaps in a backpack on the floor next to their desks; and, finally, when the phones were left in another room for the duration of the test. Results were about the same under the first two conditions: Test scores sucked. When students’ phones were stashed elsewhere, though, out of sight even if not entirely out of mind, test scores improved significantly, suggesting that proximity to cellphones was as big a distraction to students as using them.

Armed with this information, I started a cellphone discussion group with my colleagues at Mountain View, a few dozen of whom attended, sharing their frustrations and concerns—and, in some cases, despair. We petitioned the administration to do something schoolwide, but when that went exactly nowhere, I took matters into my own hands—and out of the students’: a complete cellphone ban during class. And I didn’t just ban them. I made students turn off their devices, stow them in their backpacks, and leave the backpacks piled on a counter on the far side of the room. This included smart watches and earbuds. For any kid who didn’t have a backpack and needed somewhere else to store their electronic device, I hung a shoe organizer with cellphone-sized pouches on the wall next to my desk.

I sent the policy out to all students and parents before the start of the school year and answered questions about it during orientation night. Most of the parents said they were on board, though I’m not sure they believed I would actually follow through. The incoming students, horrified, gripped their phones tighter, as if afraid I might snatch them away right then and there.

There were a few kerfuffles. A parent who’d been working at the Navy Yard in D.C. during a mass shooting insisted that her son be allowed to keep his phone with him at all times in case someone attacked the school and he needed to call her to say goodbye. School administrators ordered me to make an exception, which of course I did. The kid spent all term sneaking out his phone anytime he thought I wasn’t looking, though I don’t suppose it mattered too terribly much. Everybody else’s devices were still tucked away in their backpacks, and the kid’s mom was writing most of his assignments for him anyway—always A+ work, too.

Then there was the girl who said she was having her period and demanded access to her backpack in case she needed a tampon. She complained about it to the assistant principal, who forwarded the complaint to me. The next day in class, I sent the boys out of the room and told the girls I was adding an amendment to the cellphone policy, to wit: When they were on their periods they could either 1. Keep tampons in their pockets, or 2. Leave their phones in the shoe organizer pouches and let me know they might need access to their bags. That seemed to settle things down, though the assistant principal later scolded me for discussing menstruation with the girls, and for leaving the boys in the hall unsupervised.

Students were universally pissed off about the ban for the first two weeks. A handful kept their phones in their pockets, confident that I wouldn’t be patting anybody down, but since they couldn’t resist the impulse to pull them out while class was going on, I inevitably caught them in the act. Sanctions followed accordingly. I’d read enough about classroom management techniques by then to know that I had to set firm expectations from the beginning of the term, so I didn’t cut them any slack. And, as I’d hoped, after those first couple of weeks, the kids—to their astonishment—mostly got used to not having their phones.

Not that I was always a hard-ass. I did give a kid a break, sort of—just the one kid, and just the one time—when he “forgot” to put his phone in his backpack and reflexively pulled it out of his pocket to look up something in answer to a question I asked the class. He may not have actually said the words “Oh, shit. I fucked up”—he was sitting right in front of me with nowhere to hide—but he might as well have.

I gave him two choices. Either accept the standard punishment—a phone call to his parents and a day of in-school suspension—or balance the offending phone on his fingertips for the remainder of the class.

Zen master. Cult hero. Class clown. High school legend. Who can say? All I know is that he managed to pull it off—for an entire hour—including the 20 minutes his table group spent in the front of the room performing a research presentation song and dance.

At the end of the term, when students filled out anonymous course evaluations, half said they thought the policy was stupid, pointless, fascistic, a violation of their right to have their own personal stuff, and if anything had happened to their beloved cellphones they would have sued me and the school. Nearly as many, though, said they’d been relieved not to have to think about their phones all the time—the messages, the social media notifications, the gravitational pull of the things.

I don’t know that any test scores improved, or that my students had fewer “ADHD-like symptoms,” were happier in social situations, became more trusting of strangers, or grew closer and more communicative with their parents. (And I don’t want to know if they started having more sex or checked their iPhones less often while doing it.) I just know my classes that year were exponentially better, in part because I no longer had to be the cellphone police, constantly on the lookout for kids sneaking them out of their pockets to text one another, schedule bathroom assignations, stream dumb shows, record stuff, watch porn, plagiarize, cheat.

And in part because my students were free to engage with the world and the people and the lessons right in front of them, and for that short hour and a half every other day no longer Pavlov’s hapless pups, salivating over random stimuli—all those iPhone dings and buzzes and riffs and trills carrying the empty promise of a treat.

***

Steve Watkins is co-founder and editor of PIE & CHAI, a professor emeritus of English, a longtime tree steward with Tree Fredericksburg, an inveterate dog walker, a recovering yoga teacher and co-founder of two yoga businesses, father of four daughters, grandfather of four grandsons, and author of 15 books. His author website is http://www.stevewatkinsbooks.com/.