Suite Virginia

By Ken McFarland

Two world wars and an unwavering devotion to the godlike Franklin Roosevelt cemented a strong bond in my deeply Southern family to the United States of America—a bond that I inherited. Yet underlying this has also been a deep and abiding love of our Virginia homeland.

For many people, that embrace of the Old Dominion has also meant near ancestor worship for those who fought first on the side of Virginia, and second for the Confederacy, and I don’t suppose I was any exception—growing up listening to my great-grandmother Julia Russell’s stories of those in our family who wore the gray uniform. Born in 1867, Granny was my best friend and sometimes defender, once tossing snuff in the face of a neighborhood kid who was bullying me. She also firmly cemented my connection to my great-great-grandfather James Russell, who before he became her father served as a private in the 51st Virginia infantry regiment, a group of Southwest Virginia boys. Unlike many Southerners, Granny never called it the War Between the States. She insisted on referring to it as the Civil War, as did Robert E. Lee, and I always figured that between the two of them they knew what was what.

I listened raptly to Granny’s account of how Jim Russell fought the boys in blue at the 1864 Battle of New Market on a Shenandoah Valley battlefield notorious for its muddy, hazardous ground. I recall her telling how he broke his leg when he stepped into a “cow hole,” a crippling event that pulled him out of combat for the rest of the war. Listed as “shoemaker” in the 1860 census, Jim Russell spent the final months of 1864 into 1865 cutting leather and sewing footwear for fellow Rebel soldiers.

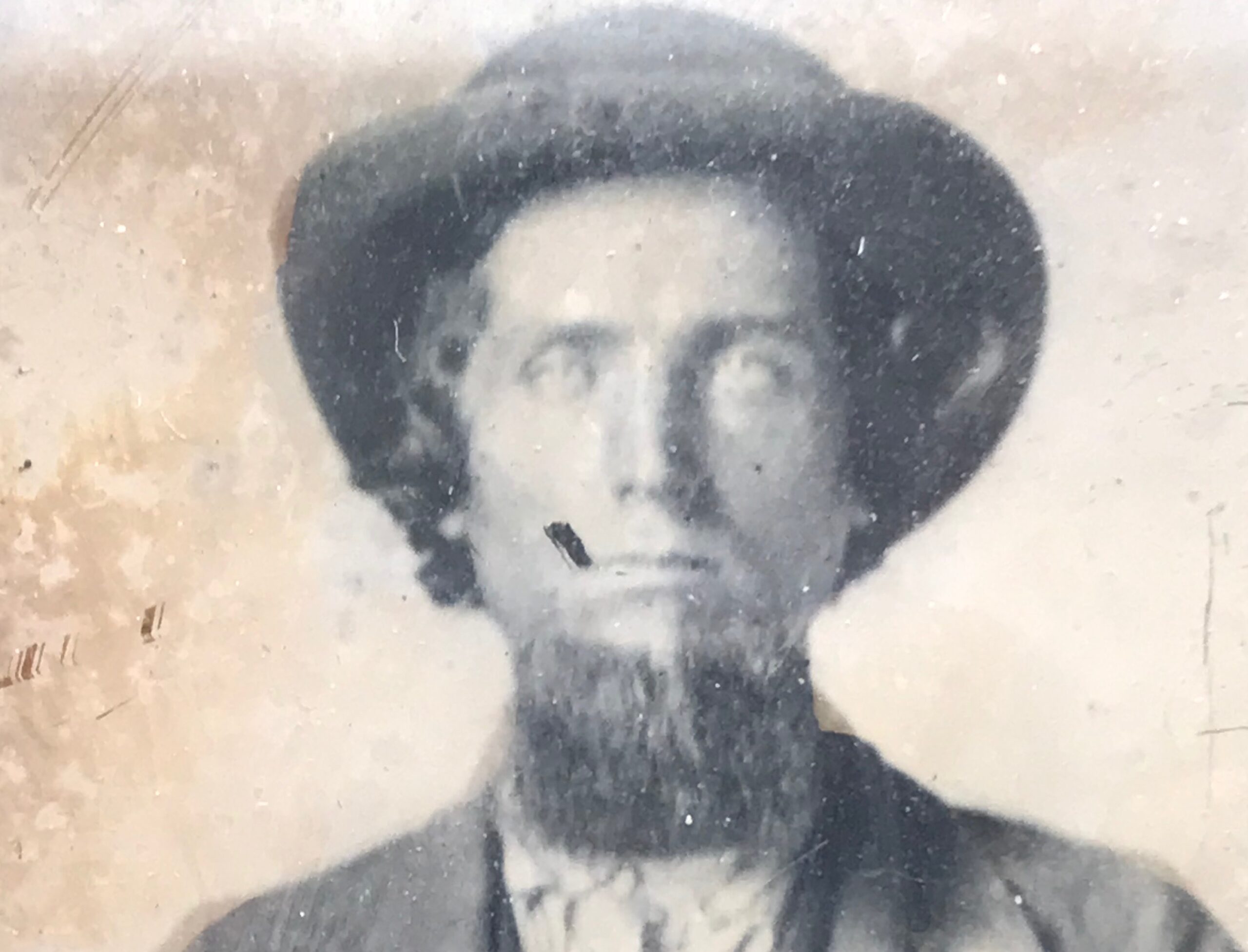

Other stories about Jim Russell’s wartime experience are lost to time, but I did inherit his Civil War Bible, along with a period ambrotype to remind me of his stern presence. By the time Granny Russell was born he had settled into a life of farming and shoemaking in Grayson County, plus off and on preaching at the Primitive Baptist Church, the war having left him with a limp and a lifetime of stories to swap with other Virginia veterans. My grandmother, Mamma Lula, only recalled him as having been “a crabbed sort of a man”—“crabbed” pronounced with the stress on two syllables. He died in 1913 in Kentucky, where many natives of his part of the Old Dominion had also emigrated.

I don’t remember any early childhood concerns or even much thought given to the causes of the conflict that sent Jim Russell off to war. In school our teachers didn’t talk much about slavery, except perhaps a random allusion to “kind masters” and “happy slaves.” I’m pretty sure they had all read and seen Gone with the Wind. A photographic recollection survives, however, from a visit around 1950 to a large, abandoned plantation house in Amelia County, Virginia. As sharp as Granddaddy Russell’s ambrotype is a mental image I still have of a small cellar room with a U-shaped bench along the sides. Manacles hung from the walls. I think even then a few tiny scales may have begun to fall from my eyes.

Only in recent years have I picked up details about my other Southern great-great-grandfathers. I knew they probably saw service, but Ancestry.com has filled in big information gaps. One thing I learned was that my granddaddy Kelly Harrell’s own granddaddy, James Arthur Harrell, enlisted in the 45th Virginia Infantry. Captured in June 1864, he was a Union POW until he was freed in a prisoner exchange a year later. He lived on until 1910, his gravestone with a Rebel flag making clear his allegiances. How much he thought about causes must remain murky, though a belief that he was defending Virginia was probably big in the mix.

Moving to my Eastern North Carolina ancestral side, another “great-great” Civil War soldier shows up in Northampton County and was the grandfather of my “Granny Mack” McFarland, born Maggie Cornelia Draper in 1882. The forebear in question was Solomon Draper, a private in the 32nd NC infantry. Joining up at the creaky age of 40 in February 1863, Granddaddy Sol was wounded in July ’63 at Gettysburg and taken to the Fort Delaware Union POW camp. And there he died on Aug. 24, 1863. His fading thoughts are also a secret of the grave. However, family sentiments seem evident in the naming of a son, Jeremiah Beauregard Draper, born in May 1861—clearly an homage to Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard from Louisiana who one month earlier, in April 1861, had led the Southern forces to victory over vastly outnumbered Union defenders at Fort Sumter.

I could continue to roll out stories of Virginia and North Carolina Rebel ancestors, though no tales hold the pathos of Sol Draper’s dying weeks, and no letters survive to help me better understand their sense of cause and mission. Did they believe they were defending the right to keep fellow humans in bondage? For that matter, did they see the enslaved as fellow humans? As far as I know none of my ancestors were enslavers, yet I would guess that if some act of providence had gifted them a large plantation they would have jumped for it. That was, after all, the pinnacle of the Southern agricultural economy, and they were all farmers.

University history training has helped me to look on the past as dispassionately as possible, and while I struggle to understand what was in the heads of my Russell, Harrell, Draper, and other named forebears, I also know my 2024 perspective is almost certainly not the outlook this same me would have had in 1861-65. For one thing, I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t have left farm, family, and friends in Virginia for a new life in the North as I did several years ago. I still live there.

Unfortunately, as I look around lately, it appears that many 2024 Americans and particularly my fellow Southerners don’t seem to be thinking much differently than their 19th-century predecessors. Witness for example the school board in Virginia’s Shenandoah County that recently re-renamed a couple of schools back in “honor” of the Confederate generals (and native sons) Lee, Jackson, and Ashby, for whom they had previously been named.

These days I live in Brandon, Vermont, a town proud of its abolitionist traditions, where on top of the Civil War monument stands a New England Yankee soldier helping to commemorate Brandon’s troops who served and died fighting men like my great-great-grandfathers. I’m certain that New England Yankee depicted in the statue was on the right side of the matter, and I feel good about living under his shadow. Not all Vermonters were keen on abolition, of course, and that particular soldier might have given little thought to the sufferings of the enslaved. He fought to preserve the Union, and in the end that also meant a Union that would end slavery with the 13th Amendment—something that would have been impossible in 1860 or if the Confederates had prevailed.

I hold no animus for my secesh forebears. As far as I know, they committed no such atrocities as Tennessee’s Fort Pillow massacre, where Confederate troops under the command of KKK founder Nathan Bedford Forrest slaughtered 300 mostly African American soldiers who had already surrendered. Instead, my great-great-grandfathers were simple foot soldiers, serving with their friends and family members who also wore the gray. One died that I know of, but the rest lived pretty ordinary and mundane lives—with a daughter on one side who had a daughter, who had a daughter who was my mother, Ruth Virginia Harrell, and with a son on the other side who had a daughter who had a son who was my father, Robie Brydon McFarland. And then they had me.

***

Ken McFarland, who reports for Pie & Chai from a small town in Vermont, was born in Martinsville, Virginia, and grew up in Durham, North Carolina. Below is a photograph taken of him in 1977 when he briefly had a National Park Service job as a Civil War re-enactor—on the Union side. The title for this essay is taken from Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War, by the late Tony Horwitz.

***