“A hole is a hole is a glorious hole.”

By Bucky McMahon

After school we siblings formed an eight-legged crocodile and trooped across the backyard, headed for the gully and the Tarzan vines. Patrick led with Eileen beside nipping at his ear. He always had a theory to expound; she felt a duty, as the eldest, to sandbag his dirigible flights with a contrary view. They were like a two-headed Cerberus, Eileen and Patrick, yoked by perpetual proximity but ever in conflict. Molly and I brought up the rear, mostly mute but exchanging little looks of sympathy and conspiracy. The time of the gully was the beginning of our years-long love affair.

Possibly none of this is accurate geography. Our little house faced south towards Atlanta; crossing the backyard, skirting a ruined farm fence of post and wire, you struck north towards wilderness and the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. To the west a dirt road led to a haunted barn and a fabulously fecund frog pond. The way to the gully was northeast, across a scrubby red-clay field still stunned by Sherman’s March (Patrick said), every bordering hardwood a Laocoon beset by kudzu. It couldn’t have been far, with our little legs: up a hill and then down a gentle slope, to the precipice of the gulley, and then down through a slot where the bank had caved in, down into the shadows of the grottoes carved by the sinuous flow of the creek.

We would rock-hop upstream to the fallen tree that formed an arching bridge. From its pachyderm back, we could grasp thick hanging vines and swing out over the creek and back to the tree, risking life and limb, it seemed, laughing and yodeling our Tarzan calls. This was the biggest fun we knew—some time on the Tarzan vines, and then poking about on the floor of the gully–when we were little and lemur-eyed with wonder.

At every turn of the creek, the bank was undercut and a profusion of roots protruded from the clay like stalactites. Here in these shadows the creek would pool– grotto and spring—and the pools were inevitably populated with the little cryptozoans who were my special delight. Each pool was a pocket kingdom, the crayfish the natural kings, mustachioed as on the playing cards, bulked in armor, claws at the ready. Minnows, with their Betty Boop eyes and gossamer gowns, were the ladies in waiting. And the little mottled green newt, my favorite, was the court jester, always discovered hovering in mid-leap, fingers splayed in mock amazement at its own agility. As I leaned close, myself now the storybook giant, the salamander fool would conclude its program of entertainments with a flick of its quicksilver tail and squiggle away under the leaf litter. The minnows too would scatter, silently shrieking. King crayfish, with a courtly bow, would back away into deeper shadow, no valor lost. And so on to the next pool.

What strikes me now, a half a century and more later, is the richness amidst poverty, the gully not even really a natural place, yet each niche was filled by a remarkable denizen, a derelict site scattered with jewels.

Around the same time of the Tarzan vines and the gulley, first and second grade, Santa Claus brought me a slide projector machine with accompanying slides, book, and LP, the multimedia package entitled “Digging for Dinosaurs.” The LP, with narration by Walter Cronkite, opened with the savage kettle drums and frenetic orchestration of Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” as if to say, hold on little fella, cause this is some powerful shit. Hearken back now some 150 million years ago to the age of the terrible lizard. I would sometimes play the set until smoke rose from the overheated projector.

All of this, the biophilia, the subterranean views from down in the gully, Stravinsky’s drums and Cronkite’s basso profundo, accompanied in me a mania for digging, ostensibly for dinosaurs, but mostly for the simple pleasures and the minor miracle of the ever-enlarging hole itself. The excavations would begin as solitary affairs, a boy and his shovel, but as the pit advanced in depth and drama, the sibs would come around to gawk and kibbutz. Eileen, a one-girl Greek chorus, would speak of the wrath of Daddy, when Daddy came home. But Daddy was out of town when holes got started. Patrick perceived the genetic compulsion—the Irish, the spade, the spud. Eejits like you built the railroads. Molly would busy herself in the hole with a trowel, cutting cubbies into the shaft and storing imaginary comestibles. Down in the cool depths, inhaling the odor and ordure of the intimate earth, I dug on, snicking through roots, halving worms, dislodging the pallid grandmotherly grub. The geological record revealed itself in colored bands of earth like an inedible version of Neapolitan ice cream.

A hole is a hole is a glorious hole. But when you connect one hole to another by tunnel it is an adventure. At the lateral turn the spirit quickens; one’s inner badger awakens in the overhead environment. At even the smallest scale there’s audacity in a tunnel. Word of my folly spread, and other neighbor kids arrived at the rim of one or another hole to jeer or, caught up in the gratuitous stupidity, pitch in. On hands and knees in permanent dusk, biting at the clay with the blade, thrusting the dirt back between our legs like terriers, I and whoever else had been seduced by the architectural beauty and logic of the arch being scraped out overhead, strived for the moment when our tunnels would meet, for the vision at last of a hand bursting through, grimy fingers fluttering, grasping, flopping like a fish in the sudden free space. Hail fellow well met! Be ye zombie, vampire, or Jesus H. Christ!

Then there was the magic of wriggling through. Shouldering the dark canal, the iron of the soil like the iron of blood. I can still invoke the willies by remembering and reckoning the chances of a cave in, several tons of Georgia clay collapsing with a sigh onto the grave of the unknown moron. Could there be a more brutal expression of the human compulsion to get from point A to point B; a more claustrophobic version of the hero’s journey through the clashing gates of duality at its very root—the thing of the earth, and the no-thing one could make in it with a shovel? I loved it. But I hadn’t then, and still lack, the gift of true fanaticism. Over the years I probably only made three versions of these connected holes. They were my first sculptures.

I think of these things, the holes, the gully, because I’ve had the dream again, one that must be, however varied in particulars, universal in essence. I think of it as the anti-travel-anxiety dream, one filled instead with the pleasures of free locomotion towards a place of belonging. There’s a growing sense of recognition, of deep-rooted familiarity, and a quickening of the heart, like nostalgia played backwards and suddenly making perfect sense. In this dream of arrival, nothing has been permanently lost.

T.S. Eliot gives his directions in the first stanza of the first of the Four Quartets, “Burnt Norton.” “Quick, said the bird, find them, find them,/ Round the corner. Through the first gate,/ Into our first world….” And here’s the poet Czeslaw Milosz, in a memoir: “I was looking at a meadow. Suddenly the realization came that during my years of wandering I had searched in vain for such a combination of leaves and flowers as was here, and that I have always been yearning to return.” Or Marcel Duchamp’s last work, “Etant Donnes: la chute d’eau, le gaz d’eclairage,” his peephole construction. The sprawling nude holds a lantern as if to guide the viewer beyond her exposed vulnerabilities to a distant rather twee yet enchanting waterfall, the source of life and the goal of life’s journeying. Or Watteau’s “L’embarquement pour Cythere.” Etcetera etcetera throughout art history.

For me the journey begins in a familiar forest, always sloping downwards towards an even more familiar ravine, which will inevitably conclude at the edge of—yes!—the gulley, the hole, the pit, the mine, or fort, or whatever it is: the project! As far as the scheduled digging goes, I can only say that I have been gone longer than I should have been. Though here I am, back at last. I can scarcely hope that the project hasn’t been abandoned. Sometimes it seems to have been. Yet there are signs of progress down there, evidence of achievement, new chambers. Work has somehow been done in my absence, good work. But in the best of these dreams, they are at it still. I cannot tell you who they are; I can never remember their faces. I don’t even really know what we are doing in the underground, only that it feels necessary and true. I can tell you there is no fear, no sense of even the possibility of futility or failure, nor any anxiety to complete the task, only a simple, clean appetite for the work itself. In a perfect blend of being and doing, in pleasant camaraderie, of the sort long sought after, I take my place among the workers of the underground and we get on with it.

***

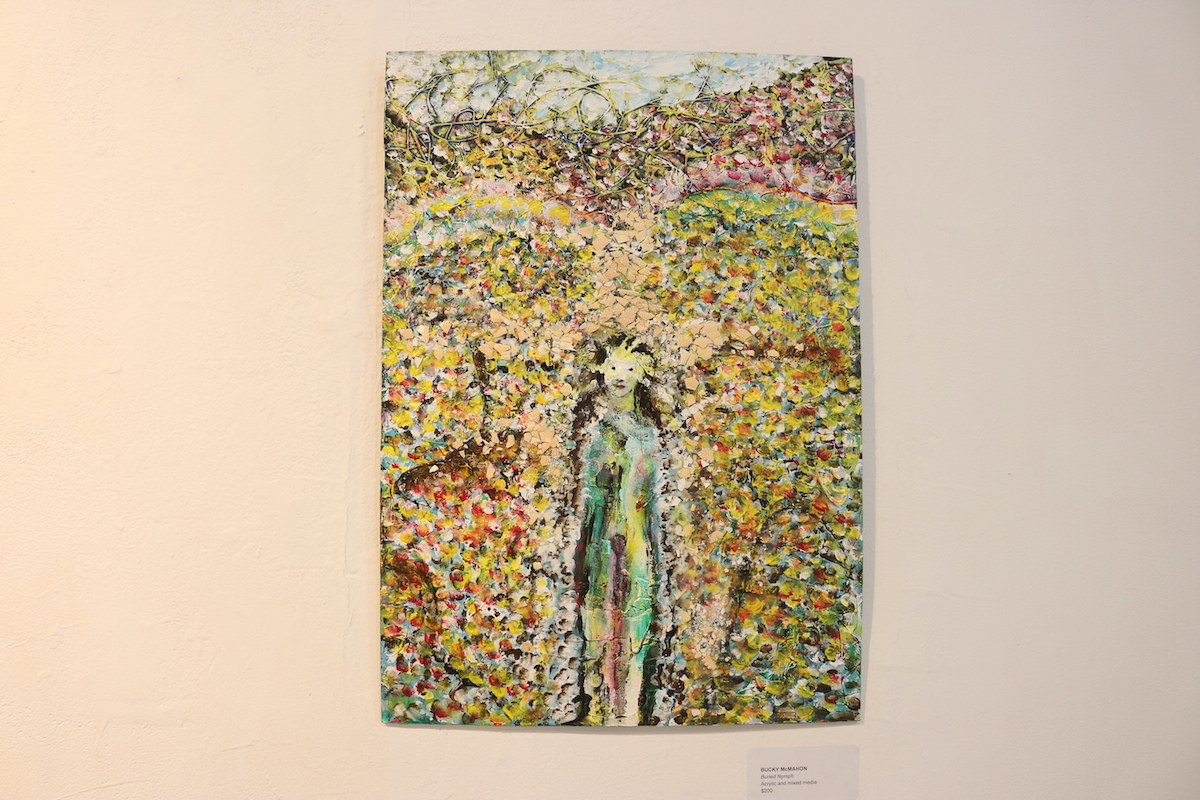

Bucky McMahon writes, paints, and sculpts in Atlantic Beach, Florida. While studying Creative Writing with Jerome Stern and Janet Burroway at The Florida State University, he wrote a humor column, “Barmadillo,” for the Tallahassee Democrat. As a Contributing Editor for Esquire, and a Correspondent for Outside Magazine, he reported from many exotic and tragic locales around the world. His feature stories have been anthologized in the “Best American Writing” series, for sports (twice) and travel. He is the author of Night Diver, a collection of adventure yarns and cartoons based on dreams.