Roadkill Yoga

By Alison Zak

[From Wild Asana by Alison Zak, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2023 by Alison Zak. Reprinted by permission of North Atlantic Books.]

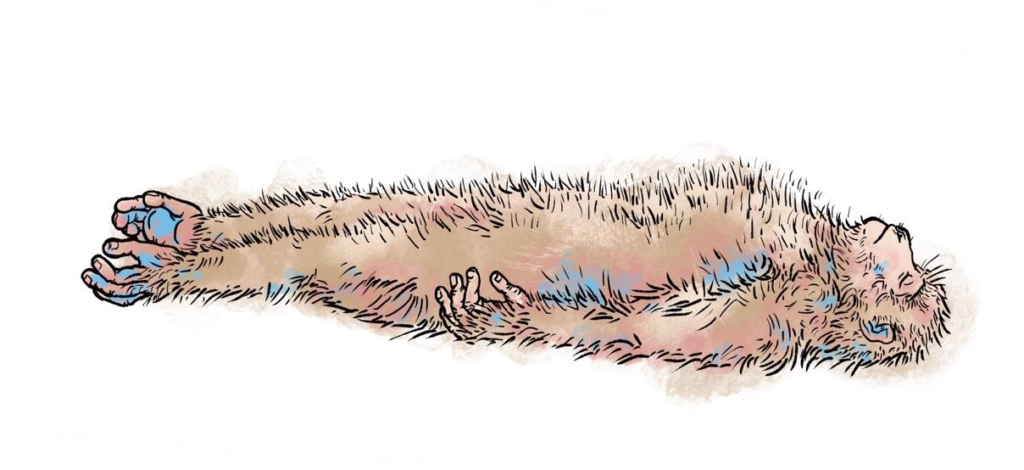

Savasana, also known as corpse pose, is practiced lying on the back with the spine in alignment, the feet relaxed as the legs rotate externally, and the palms facing up with fingers gently curled. When I prepare for savasana I fidget and wriggle until the back of my head is flat on the floor and my arms rest at the preferred angle to my supine body. I relax the muscles in my face for the first time that day, maybe for the first time this life. Author Lyanda Lynn Haupt writes that savasana is “a reminder that the world can do very well without us for a short time, and will eventually do very well without us altogether.”

Benefits of savasana may include, most notably, a positive effect on the parasympathetic nervous system that allows our bodies to rest and digest. According to expert yoga teacher Judith Hanson Lasater, this one pose has the potential, when practiced regularly, to refresh our mood, reduce stress and anxiety, slow the effects of aging on the body, improve sleep, and reduce blood sugar and cholesterol levels. As the end of savasana signals the transition away from our asana practice, death (of the physical body or, instead, a more metaphorical kind) is one of the most important transitions we and other beings experience.

Savasana need not represent only the human corpse. The mysterious exception of some monkeys aside, animal bodies of all shapes and sizes litter the earth in various stages of death and decomposition. We observe many more beyond-human corpses in our lifetime than human ones. We are destroyers. Sometimes we create a corpse with our shoe, a tire, or even with our own hand. I have slapped countless mosquitoes (on purpose), accidentally rolled the wheel of a gate over the soft body of an anole, and hit a raccoon, a rabbit, and a mourning dove with my car. That last one was the most devastating. I could no longer see the road to drive as I wailed, “I’m so sorry!” on repeat as my mind replayed the spray of feathers near my front right tire on an endless loop. I called my brand-new boyfriend, sobbing uncontrollably. (He married me anyway, bless his heart!) If suffering inevitably exists, as the first Noble Truth in Buddhism advises, then we must accept that we cannot exist without harming other beings. All we can do is try our best to limit the harm.

On my commute one morning, from my suburban home to a more rural county to the west, I counted five carcasses (and nearly missed a live squirrel). There were two deer, a red fox, a Canada goose, and a raccoon. With each corpse I passed, I wondered how many more animals were hit and had crawled just far enough away from the grimy medians and gravel-strewn shoulders to die under shrouds of grass. I hoped their lives, no less valuable than mine, were long and their suffering short. The bloated doe on which the crow fed had fawns to carry and birth, nurse, and groom. She had shrubs to browse, hunters to hide from, and coyotes to avoid. She had sunsets to watch with eyes like dark pools from her bed of stomped-down sumac and little bluestem. Her purpose in life could not have been to teach a driver not to speed.

I knew how deeply I loved my husband when I saw his reaction to a snake run over by another car, as we traveled Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park. It happened so fast. I doubt they meant to hit the snake, though I know some drivers do aim for wildlife in this horrific manner. The road was twisty and turny, and we were passing another car headed in the opposite direction as the snake chose that second to cross the road. We watched the tire of the car hit the snake. Then we watched the snake thrash around helplessly. Vishu squeezed his eyes shut and pounded a tight fist against his thigh as a sharp sigh escaped his lips. I might yell and point when I realize what is about to happen, but when it does, I am frozen. The expression on my face is blank. I shut down except for my mind in which the scene replays over and over for minutes, maybe hours, maybe days with fading frequency. But Vishu’s reaction was visceral and involuntary. The grief and care for a creature he never knew was written all over his face.

Yet, even after death there is life. I first suspected there was magic in savasana when I wiggled my fingers and they tingled with pleasure, gratitude, and remembrance that they were indeed a part of this body— and very much alive. An arguably more “animal” variation of this pose is the side-lying version in which the head is supported by blankets and the knees hugged in toward the chest. With my body in this position, I feel curled up, cozy, and safe. Many teachers transition their students out of savasana with a minute or two of side-lying before they sit up again. In this way, we move from corpse to the fetal position. We are reborn. Our eyes flutter open, we fold our hands in front of our hearts, and we stumble out of savasana and back into the world. Into our cars to sit in traffic.

Art by Jasmine Hromjak

***

Alison Zak is an author, yoga teacher, anthropologist, and animal. She lives in northern Virginia with her husband Vishu, Meeko the dog, and Monkey and Gus the adopted budgies. In addition to her writing and spiritual practices, Alison runs the Human-Beaver Coexistence Fund and regrets that there is no yoga pose named after the incredible ecosystem engineer, the beaver. Learn more about her at www.alisonzak.com and follow her on Twitter and Instagram @animal_asana. Wild Asana can be purchased at https://www.northatlanticbooks.com/shop/wild-asana/.